Summary:

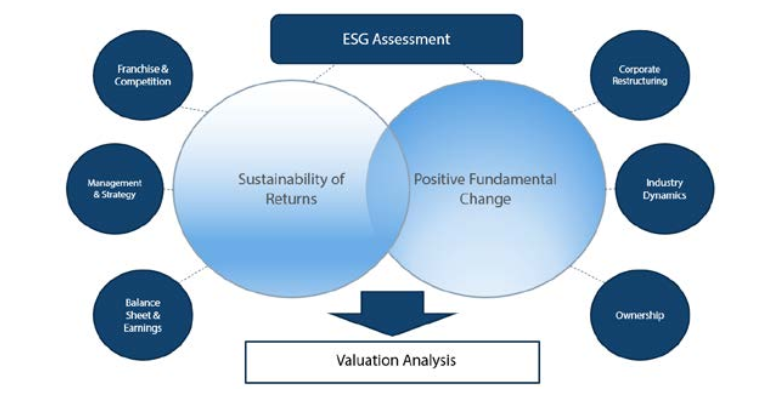

The NikkoAM Asia ex Japan equities team focuses on two core characteristics in our fundamental research; sustainability of returns and positive fundamental change. We find these are two common areas that can be materially mispriced by markets (Further detail in Appendix).

A key part of our fundamental analysis toolkit is the integration of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) materiality assessments. This helps us build the case for sustainability of earnings, risk mitigation and identifying industries or companies undergoing positive fundamental change. ESG can, but does not always, impact equity valuations.

In this piece we look at two examples of industries with very attractive long-term growth characteristics but which experienced large-scale social controversies – these events were catalysts for positive fundamental change at a time when stocks were trading at heavily discounted valuations. These were China’s 2008 milk scandal and India’s Andhra Pradesh microfinance crisis of 2010. Both cases resulted in deaths and subsequent industry and company upheaval ultimately leading to structurally lower ongoing ESG related risks in both sub-sectors. Had you backed the right stocks post these negative events returns were in excess of 20x.

Case Study 1 – The 2008 China Milk Scandal

Background:

On September 11, 2008, the Chinese government finally announced a recall of infant milk powder nationwide that was mixed with Melamine, a chemical used to boost protein content but more commonly used in plastics. Over 290,000 people (mostly infants) were poisoned and at least 6 confirmed to have died as a result of the deliberate contamination. The main reason cited was rapidly rising retail prices and intense competition amongst companies for scarce milk supplies. Millions of small, poor and uneducated traditional farmers were utilised for cheaper raw milk production. In 2006, 60% of China’s milk production was carried out by farmers with fewer than 20 cows, 35% from 1-5 cows (1).

Milk stations or distribution centres were set up to make collection more efficient but often management was outsourced and pressure to re-coup the initial outlay was intense. This together with inadequate inspections or emphasis on health and safety standards by the relevant authorities led to rampant adulteration and watering down of raw milk to increase volumes. The downstream companies themselves were willing to accept lower quality milk without proper checks and procedures given huge potential profits. (2).

Although Sanlu Group (unlisted), the market leader in the budget segment at the time, was the main company impacted (ultimately declared bankrupt in February 2009) all major Chinese milk producers were implicated including listed players China Mengniu, Inner Mongolia Yili, Bright Dairy and China Milk Products.

So how could ESG analysis have helped?

First it was about risk mitigation, secondly it was recognizing positive fundamental change to a social controversy. This occurred at both the industry and corporate level which reduced food safety and supply risks and improved the long-term sustainability of earnings profile. We focus here on China Mengniu which together with Inner Mongolia Yili were two of the eventual long-term winners.

Build-up to the crisis - Risk Mitigation:

The boom bust nature of the emerging industry had led to a decrease in raw milk supply in 2005/6 just as retail prices in China were increasing. Wen Jiabao’s statement in April 2006 “I have a dream to provide every Chinese, especially Children, sufficient milk each day” (3) led to a spike in demand. This combined with the small farmer supply structure and inadequate regulatory oversight presented individuals with every incentive to cut corners – the risk was always there. Further clues came from local media reports on abnormally large numbers of infants being diagnosed with Kidney stones in Gansu.

The biggest clue that something was amiss was insider selling. First Danone sold their stake in Bright Dairy in October 2007. There is no indication they knew of the growing risks – this sale occurred when valuations were rich across the sector and reported disputes with another JV partner, Hangzhou Wahaha Group, had made Danone more cautious on the sector (4). Next was Jinniu Milk Industry and Yinniu Milk Industry who together sold a block of shares on August 4th 2008, a little over one month before the official announcement on September 11th. Shares in China Mengniu plunged 65% when the trading halt was lifted on the 23rd September. Peak to trough Mengniu lost 80% of its value.

Chart 1

Source: Bloomberg

Reactions & Reforms – Positive fundamental change

There were a number of positive fundamental changes both at the industry level and at the company level. All combined to reduce food safety and supply risks on a sustainable basis.

Industry Overhaul:

The scandal became a national issue with concerns over other food production and exports. Health and safety inspections ramped up, became regular and mandated for all companies in the food business aided by the announcement of 400 testing centres to be built across the country (5). An emergency rescue package was put together for farmers ensuring raw milk production didn’t cease altogether as a result of the freeze in demand. Regulatory bodies were overhauled too with the director of the AQSIQ being fired and criminal prosecutions brought against those deemed responsible. Sanlu, which had been at the centre of the scandal was forced to declare bankruptcy in February of 2009.

The immediate response was followed by more structural regulatory changes including the establishment of a formal Food Safety Law (2009), a Food Safety Commission (2010) set up and finally the China Food & Drug Administration (CFDA) (2013).

Chart 2

Source: Bloomberg

Company specific – China Mengniu:

Given the scale of the crisis (impacting all major players) positive fundamental changes were required at an industry level as well as at the company level. Investors first had to establish Mengniu’s issues were not terminal.

Financial Analysis - Relatively superior governance and likely internal procurement procedures were perhaps evident from the fact that only 10% (Yili had the same) of its liquid milk samples were found to have melamine contamination vs. 100% of Sanlu’s (5). Despite this the company recalled all its infant milk formula in September of 2008, although products were back on the shelves shortly after. Its balance sheet had a net cash position before the crisis broke and although it needed to take on short term bank funding and raise debt in 1Q09 there were willing backers locally for this.

Ownership - The biggest changes came at the ownership level from 2009-14. Firstly, 10% new shares were issued which together with Mr. Niu’s (Mengniu’s founder and CEO) 10% stake sale were acquired by a consortium made up of China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs (COFCO – a state owned processing company) and PE firm HOPU 6%. This gave Mengniu fresh capital (which helped pay down debt) but also a state backer which provided further evidence that this company was going to make it through. Later, Arla Foods of Denmark, who had been a JV partner for a subsidiary venture, bought HOPU’s 6% stake. Danone then bought a 10% stake in 2014.

Operational - Internally too, improvements were made to its food safety, monitoring & control procedures but a more important change in our opinion was the 10 year agreement signed in 2009 with upstream producer China Modern Dairy for 100% of their milk supply. This was the start of large scale consolidation in upstream milk production which helped Menginu secure 15-20% of its milk from one source. In 2013 Mengniu became more vertically integrated after purchasing a 27% stake in China Modern Dairy.

Chart 3

Source: Bloomberg

Case Study 2 – 2010 Andhra Pradesh Microfinance Crisis

Background:

In early October 2010, in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, a crisis was unfolding. Several newspapers had reported on suicides amongst the poor as a result of excessive recovery practices employed by microfinance lenders. The state’s chief minister passed “An Ordinance to protect the women Self Help Groups from exploitation by Micro Finance Institutions (MFI) in the state of Andhra Pradesh” which ultimately resulted in a dramatic drop in loan collections from 99% to 20% in 6 months (1). Non-repayment of loans gained momentum leading other populist politicians to advise borrowers to do the same, further exacerbating the problem. This lead banks to tighten lending to MFI’s, limiting their ability to roll-over loans, not just in Andhra Pradesh but across other states, creating a liquidity driven bad debt cycle. A localised problem quickly became more widespread impacting nationwide lenders.

Bharat Financial Inclusion (BHAFIN, Est. 1997, previously SKS Microfinance) used the group liability model of microfinance, lending solely to women and for productive purposes (buying farming equipment, livestock, sewing machines etc.) in amounts of roughly US$100-800. It listed to great fan-fare in July 2010. The company had approximately one third of its balance sheet in Andhra Pradesh, more than its equity capital at the time the crisis unfolded. It survived but many other smaller unlisted MFI’s would go under.

NikkoAM – On-The-Ground Site Visit Jaipur, 2015

How could ESG analysis have helped? Again, we look at risk mitigation followed by recognizing positive fundamental change to a social controversy which improved the long-term sustainability of earnings profile. There are many desirable attributes to productive microfinance lending and in an under-penetrated credit economy like India there is a lot of opportunity for long term growth.

Build-up to the crisis - Risk Mitigation:

Precedents for regulatory intervention - In 2005–2006 one of Andhra Pradesh’s 23 administrative districts experienced a crisis when the district government closed 50 branches of four MFIs following allegations of unethical collections, illegal operational practices (such as taking savings), poor governance, high interest rates, and profiteering. Although this event did not spread nationwide it highlighted the risk of local state intervention (2).

Supernormal Growth & Profitability - 2009 credit growth rates were over 100% across the industry while a fully functioning credit bureau was not operating. Multiple new MFIs were being set up and granted licenses without reputable nationwide regulatory oversight igniting intense competition. This environment was a hotbed for exuberant practices and were indicative of large social risks given the nature of the business and the end recipients (uneducated poor).

Bharat Financial Inclusion IPO’d 28 July 2010 and was the largest MFI in terms of total loans outstanding. The prospectus identified growth rates were 148% CAGR from March 2006 to March 2010 pre-IPO (3). Valuations achieved at IPO clearly ignored the risks highlighted above and priced in strong sustainable growth.

Unlike China Mengniu there were no early warning signs from insider selling. The only hint may have been the sacking of then CEO, Suresh Gurumani, on October 5th 2010 without any justification from the company. It was reported in local media articles at the time that this was related to a power struggle in the firm. (4)

In Early October 2010 the first reports of farmer suicides in Andhra Pradesh started to emerge followed shortly after by the state’s ordinance against MFI’s. Peak to trough BHAFIN lost 95% of its value.

Chart 4

Source: Bloomberg

Reactions & Reforms – Positive fundamental change

Industry Overhaul:

In the immediate aftermath companies had to fend for themselves which resulted in much confusion and panic, other states joined the chorus and banks pulled funding exacerbating the problem. 4 private credit bureaus were given licenses in Dec 2010 which would eventually improve transparency and KYC checks (5). Only in early 2011 did the response start with the Malegam Committee Report. 19 Jan 2011 which recommended RBI as the sole regulator for all MFIs.

The first announcement from RBI came April 2011 that bank loans to MFIs would qualify for priority sector lending (PSL) requirements, helping partially address funding issues. Around the same time an MFI Bill was proposed although it was not tabled until 2012 and was only approved by the Union Cabinet in Dec 2014.

In the period from 2Q11-4Q12 several measures were introduced at the micro-level including a cap on fixed spread (limiting exorbitant interest rates charged and incentivised companies to lower funding costs as a competitive advantage), a ceiling on per-household lending (limiting over-indebtedness) and higher minimum capital requirements to enter the space. All these worked to lower the long-term risk profile of the sector and change the incentive structure.

Chart 5

Source: Bloomberg

Company specific – Bharat Financial Inclusion:

Capital - BHAFIN’s IPO gave it $350mn of fresh capital just before the crisis unfolded which was one reason it was able to avoid a corporate debt restructuring (CDR) and write down its bad debts over time. It reported 7 consecutive quarterly losses from calendar 1Q11-2Q13 but was able to raise capital in July 2012 supported by key stakeholders (Westbridge upped stake to 12.5%). This was used to pay down bad debts and start growing its Non-AP book. A subsequent raising in May 2014 gave the company capital for further growth.

Ownership - Vikram Akula, the founder and promoter of BHAFIN, stepped down as Chairman in Nov 2011 and was forced out in 2012 although only in May 2014 did he finally sell his remaining stake in the company. This put an end to internal power struggles and allowed senior decision makers to focus on the business. (6)

Operational changes – cost rationalisation, single state limits, IT/Tablets for better record keeping, implementing new RBI rules on collection practices and more rigorous training programs for staff.

Chart 6

Source: Bloomberg

Conclusions

Peak to trough, stocks in China Mengniu and Bharat Financial lost 80% and 95% of their value. While ESG analysis may have highlighted the risks involved in each industry it doesn’t tell you when those risks would materialise and how bad the event could be. In sectors with super-normal profits and trading at high multiples the reaction to these risks materialising can be severely amplified. We often find that on the way up the market is willing to ignore such risks and on the way down the market will avoid the sector altogether even though the risks are fully exposed. One key thing to watch is insider activity and management movements as these may be some of the first red flags that something is wrong.

While most will look at this from a risk mitigation perspective we aim to illustrate here that ESG controversies can lead to positive fundamental change, ultimately leading to better sustainability of earnings as structural risks decline. ESG controversies should not preclude someone from investing in industries with good long-term growth prospects provided one can be assured of positive change.

Not every controversy or negative event leads to positive fundamental change, but when they do occur, and in a structural growth industry, the returns can be supernormal. Had you invested in China Mengniu (H-Share) or Inner Mongolia Yili (A-share listed – hence was off-limits to most investors back then) in 4Q08 you could have made 6x and 20x your initial investment respectively. Bharat Financial Inclusion returned over 20x before recently being acquired by IndusInd Bank.

Timing the bottom is also incredibly difficult. The speed with which regulators and authorities act, the external support each company has and the nature of both earnings and balance sheet risk are some of the key areas that would have helped with timing in these examples.

We are firm believers in the value integrated ESG analysis brings to an investment process. This helps us build the case for sustainability of earnings, risk mitigation and identifying industries or companies undergoing positive fundamental change.

Where might similar events be playing out now? We are currently evaluating a number of areas including vaccines and P2P lenders in China, corporate lenders in India, political change in Malaysia– there is always something keeping us busy.

References:

China Milk Scandal:

(1) Supply Chain Issues in China’s Milk Adulteration Incident, Fred Gale and Dinghuan Hu (https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/51613/2/China%20Dairy%20industry%20IAAE%20_June2009.pdf)

(2) “Melamine in milk products in China: Examining the factors that led to deliberate use of containment” Changbai Xiu, K K Klein. May 2010

(3) http://www.gov.cn/english/2006-04/24/content_263216.htm

(4) https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB119255874945460808

(5) "China scrambles to salvage reputation amid milk scandal". Agence France-Presse. 25 September 2008.

(6) "Most liquid milk in China does not contain melamine". Xinhua News Agency. 18 September 2008

Indian Microfinance Crisis:

(1) https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/CGAP-Focus-Note-Andhra-Pradesh-2010-Global-Implications-of-the-Crisis-in-Indian-Microfinance-Nov-2010.pdf

(2) “Microfinance Institutions in Andhra Pradesh: Crisis and Diagnosis”, HS Shylendra, 2006

(3) SKS Microfinance IPO prospectus July 2010

(4) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/announcements/sks-microfinances-gurumani-sacked-in-power-struggle/articleshow/6686460.cms

(5) https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-evolving-landscape-of-microfinance-institutions-in-india/%24FILE/ey-evolving-landscape-of-microfinance-institutions-in-india.pdf

(6) https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/vikram-akula-to-bury-past-sks-trust-to-sell-stake-in-sks-microfinance/articleshow/35081145.cms

Appendix:

Definitions of Sustainability of Returns and Positive Fundamental Change

Companies exhibiting strong sustainability of returns potential typically have some competitive edge or franchise which limits threats together with good growth opportunities. Often this can be related back to the quality of management or beneficial owners, their long-term capital allocation decisions and strategies. Healthy balance sheets and earnings visibility beyond the market’s typical short term (1-2 year) focus are also key attributes.

Positive fundamental change can occur as a result of many different events. Some of the more common are industry changes, capital allocation changes (eg. M&A), management or ownership changes. We actively monitor and review such events and the likely impact on long term valuations and/or sustainability of returns. Good quality companies can go through periods of hardship and often a significant change can act as the catalyst for a turn in fortunes and improved earnings outlook.

Asia ex Japan Equity team – Summary of detailed fundamental research: