Investment through the ages

The origins of the ‘Edinburgh’ investment style can best be understood by an analysis of the role Scottish and British investment trusts had to play in the export of capital overseas from the UK in the late 19th century. In the 1860s and 1870s, Britain’s first investment trusts were set up specifically to give smaller investors access to global markets, providing them with the benefits of diversification that had only been available to very wealthy investors.

The values enshrined in those early investment trusts had a significant influence on the style of investment undertaken in Edinburgh at the time. The city came to be at the forefront of a boom in overseas portfolio investment in Britain—gaining significant share in the export of capital overseas—as the Edinburgh style of investing proved highly successful during varying economic downturns.

The values of prudence, sensible diversification and value for money served their investors well and allowed the industry to weather the Great Crash of 1929 and to prosper thereafter. It is perhaps no surprise that these values which characterise the Edinburgh style of investment continue to be passed on from generation to generation.

A brief history of time

A low interest rate environment prevailed for almost all of the 19th century and the resultant hunt for yield and an ever increasing risk appetite led to a boom in the creation of investment companies between 1868 and the crash of 1929. With British industrial infrastructure and its railway network the most advanced in the world, it was natural for investors to seek higher yields in riskier ventures abroad.

The late 19th century saw a boom in new companies investing in everything from foreign government bonds, railroad bonds, ranching estates, and submarine cable and telegraph companies to name a few. Crucially, the lessons learned from varying crises during this time enabled British and, in particular, Scottish investment companies to safeguard their clients’ capital far better than their US counterparts in the Great Crash of 1929. The Edinburgh style of prudence, sensible diversification and a focus on the long term was born out of this period and these values have been passed on by generations to influence the city’s investors of today.

To explore this further, this paper draws on academic research to assess the investment backdrop of 19th century Britain, which gave birth to the first investment trusts with the express aim of giving a new class of investor access to opportunities overseas. A detailed look at the early trust structures and portfolios can help offer insight into the values on which these funds were founded — values which came to characterise the Edinburgh style. We then track the rise of the investment industry in Scotland and Edinburgh in particular as it gained significant market share in the investment industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Finally, the success of the industry in navigating the Great Crash of 1929—particularly when compared with peers in the US—can help us fully understand how these investment values became so embedded in the city’s investment culture.

Investment opportunities in 19th century Britain

An investor landing in the present day from 1868 could be forgiven for thinking that in terms of interest rates and risk appetites, not a great deal has changed. The world’s creditor nation at the time (the UK) had seen a very prolonged period of declining interest rates which left the long-term government bond yield at 3.2% (down from 5% in 1800). As a result, there had been several waves of overseas investment—largely funded by the UK’s upper and middle classes—as investors chased after growth in new ventures with higher yields.

In the 1820s, Rothschild and Barings led debt issues for the governments of Austria, Germany, Russia and the emerging republics of Central and South America. By 1843, British investors held about GBP 120 million (c. GBP 7.2 billion in today’s purchasing power) of foreign bonds. Large scale foreign infrastructure bonds also took off in the 1840s during the US railroad boom and substantial amounts of UK capital went to the US at this time. Following on from this, British capital was the cornerstone of the infrastructural development of the British colonies and South America from the 1870s onwards. The scale of this can be seen by the fact that by 1913—with the UK at the peak of its financial power—foreign securities represented 60% of the London Stock Exchange’s market capitalisation. Low interest rates, a growing risk appetite and higher yields abroad had meant a significant export of British capital during the century.

Throughout this period between 1820 and 1865 however, there were significant setbacks. The US railroad industry turned from boom to bust, individual projects and companies failed and governments occasionally defaulted. What became clear was that the very wealthy investors with a range of different investments were able to cope with the shocks and see the fruits of their other long term investments more than off-set these losses. Those who were less well-off were often wiped out when too focused on individual issues or specific industry or country risks. The benefits of diversification – a key foundation of ‘Edinburgh style’ had been seen for the first time.

1868 – The UK’s first investment trust is formed: Foreign and Colonial Government Securities Trust

The specific aim of the Foreign and Colonial Government Trust, as stated in the original prospectus, was to ‘give the investor of moderate means the same advantages as large Capitalists, in diminishing the risk of investing in Foreign and Colonial Government stocks, by spreading them over a number of different issues’. The Times also admired the decision to limit yearly dividends to a level which would allow reserves to be built up such that future dividends might be maintained. Although not a Scottish trust in its own right, two of the key foundations of Edinburgh style were core values for the very first investment trust listing in the UK. Namely diversification and prudence.

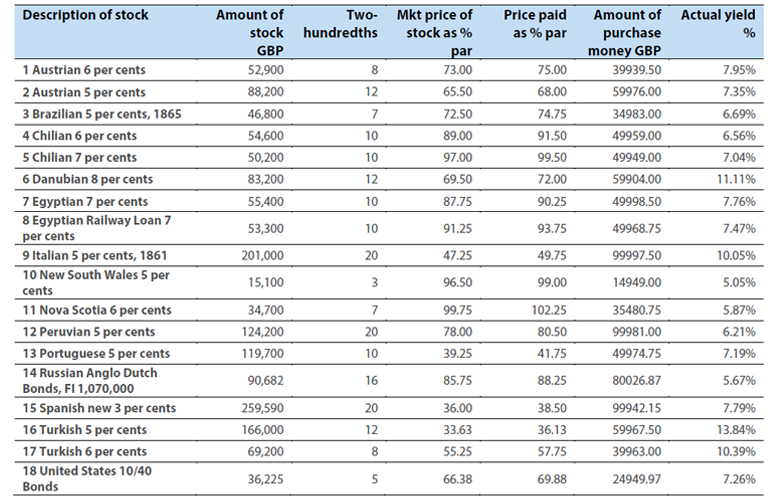

Table 1 shows the initial portfolio of the Foreign and Colonial Government Trust in 1868 – the observant reader might notice that country risk premia don’t seem to have changed that much! Colonial securities in Nova Scotia and New South Wales were yielding around 5%, but the riskier markets of Southern Europe (Italy) as well as places like Turkey were offering yields of almost 10% or higher! The US at 7% relative to Peru’s 6% looks to have been a good buy, however.

Table 1 Foreign and Colonial Government Trust schedule of investments, 1868

Source: Janette Rutterford ‘Learning from one another’s mistakes’ p 160 Table 1

The ground rules for the UK’s first ever investment trust will also sound familiar to today’s investor. As outlined above, transparency was a key feature — investors could see the whole portfolio. Individual holdings were limited to a maximum of 10% and while the portfolio targeted an overall yield of 8%, the income payable to investors was set at a 6% target. The difference between the two figures was to be used as a reserve to ensure payments could be maintained even in light of unforeseen events. There was transparency in fees also — set to an explicit level of £2,500 per trust, which was equivalent to 0.5% of the underlying assets.

The founding values of transparency, prudence and value for money were set to provide individual investors the benefit of exposure to a reasonably diversified selection of international stocks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these values proved popular with investors and the initial issue was met with great success. Indeed, Foreign & Colonial’s success was replicated with a rash of new trusts which copied this model to raise capital between 1868 and the end of the 19th century.

The role of Scotland in investing overseas in 19th Century Britain

While the Foreign & Colonial Government Trust established on the London Stock Exchange in 1868 set the model for collective investment schemes aimed at investors of ‘moderate means’, investment companies with the aim of investing overseas had started to form in Scotland from the 1830s. The first British-sponsored foreign ‘investment company’ was in fact Scottish. The Illinois Investment company was formed in Aberdeen in 1837 by George Smith, an Aberdeen businessman who migrated to Chicago in 1833. Smith’s arrival in Chicago coincided with a land frenzy and his business associate Alexander Anderson successfully promoted the real estate investment venture to the wealthy community of Aberdeen. Riding the property boom of the US Midwest at the time proved highly profitable with Smith going on to establish five separate Scottish investment companies by 1840, channelling GBP 380,000 from Scotland to the US and returning annual dividends of between 12 and 15 per cent.

Similar ventures aiming to invest in Australia were also successful in raising capital during the 1840s but financial returns were much more mixed. Scots continued to favour America as a favoured destination for overseas investment throughout the period. Ease of financial exchange, kinship, common language and a familiar legal system were all likely contributing factors for this preference. Improving communication and transport technologies (the telegraph and the steam ship) meant that it was becoming easier to track investments and communicate more quickly across the Atlantic. In addition, it was common for American states to issue bonds denominated in pounds sterling through UK-based banks.

While these early investment companies set precedents for Scottish foreign investment, it wasn’t until the 1860s and ’70s that both foreign direct (FDI) and portfolio investment really accelerated. Glasgow thread manufacturer J.P. Coats established mills in the US, Canada, Russia, Austria and Spain while the jute manufacturing Cox brothers built the first jute spinning mill in Calcutta in 1855.

These ventures took advantage of close proximity to raw materials and gained access to growing markets to counter-balance increasing trade tariffs. These were dominant players creating a global manufacturing network which, in the case of Coats, propelled them to be the third most valuable company in the UK stock market at the turn of the century.

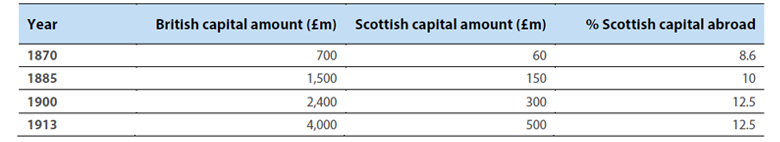

If the 1850s and 1860s were characterised by growing levels of FDI by Scotland’s leading manufacturers, it was the early 1870s which saw a burst of portfolio investment that marked the beginning of modern Scottish foreign investment via investment trusts. Drawing on the values and success of the Foreign and Colonial issue in 1868 along with a severe economic crisis in America in 1873, astute Scottish financiers recognised that this was an opportune time to diversify away from investment in British railroads towards more lucrative opportunities in the US. This ushered in a rapid acceleration in the amount of capital invested overseas from Scotland from 1870 onwards. Foreign investment coming from Scotland rose from GBP 60 million in 1870 to reach GBP 500 million by 1913.

Table 2 Comparative estimates of British foreign capital investment, 1870 – 1914

Source: Imlah, Economic Elements in the Pax Britannica, pp. 72 – 75; Lythe and Butt, An Economic History of Scotland, p. 236.

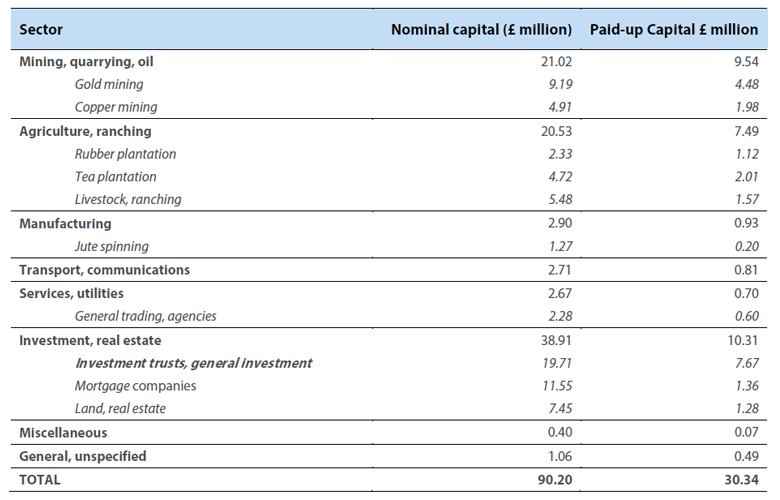

As Scotland was taking the lead in providing portfolio investment abroad from the UK, Edinburgh came to be the leader within Scotland. Table 3 shows the scale of investment companies active in Edinburgh during this period. It had become the centre of Scottish financial asset management and was playing a large part in the control of British foreign investment. Its natural advantage as the home of the financial and legal professionals served to provide expertise but also sources of capital. Indeed, the figures in the two tables represented here likely underestimate the amount of capital invested overseas from Scotland at this time, as the figures ignore amounts invested in ventures listed in London.

Also from Table 3, the success of the investment trust sector during this period is, in itself, quite remarkable. These trusts arguably proved so popular with investors due to their emulation of the values represented in the Foreign and Colonial Trust founded in 1868. By staying true to these values during the Barings debt crisis of 1890, longer established investment trusts were able to weather the storm better than some of the more risky ventures which had appeared later in the period (in 1890, trusts formed after 1880 saw asset values fall 29% while those formed before 1880 fell only 14%). These values of prudence, sensible diversification, a focus on the long term while offering value for money to every day investors had allowed Scottish investment trusts to survive and thrive in a period of adversity. These were also values which stood the industry in great stead when it came to the most challenging economic event of all – the Great Crash of 1929.

Table 3 Nominal and paid-up capital of companies registered in Edinburgh by sector, 1862 - 1914

Source: Schmitz, ‘The Nature and Dimensions of Scottish Foreign Investment’. P. 47.

The roaring ’20s and the Great Crash of 1929

The 1920s saw the largest new issue boom in British investment trusts with 103 trusts floated between 1924 and 1929. This was dwarfed, however, by the rapid emergence of the investment trust industry in the US at that time. Originally, the US trusts adopted structures and operating models which were based on their English and Scottish predecessors. With the stock market taking off, their popularity in the US soared.

Using techniques developed for the sale of Liberty Bonds during World War 1, more than 7,000 securities dealers and 30,000 banks bid against each other for new issues. Investment Trust flotations in the US offered an infinite number of new shares and as the supply of new industrial and commercial common stock began to dry up, new US investment trust companies were floated to invest in other investment trust companies, creating a pyramid effect. US trust capital structures became ever more complex, cross holdings increased and management fees ballooned. Some US investment trusts sold at a premium to par value of as much as 200% — a par value which itself may have included investments in other trusts also at a premium!

It was 1928 when the US trust sector overtook the UK equivalent in terms of assets (USD 1.2 billion versus USD 1 billion). Yet by the end of 1929, the US trust industry stood at USD 7 billion invested in 675 investment firms — a roughly 6-fold increase in just over 12 months. As we know, this came crashing down thereafter with the Economist noting that no US investment company suffered a loss of any less than 75% of their assets.

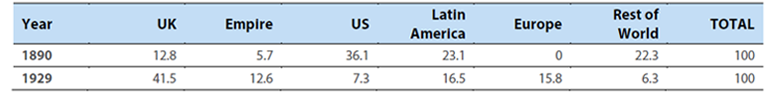

As discussed previously, the values laid down in the early UK-based trust issues and the experience learned from the Barings crisis of 1890 served to greatly limit the damage suffered by the industry in the UK during the crash. Indeed, as Table 4 shows, UK-based trusts had made a significant shift away from the US in the years leading up to the Great Crash.

Table 4 Geographical split of British investment trust assets in percentage terms

Sample of 10 companies in 1890, 20 companies in 1929, book value of funds

Source: The Economist, 20 December 1937, p. 365

In 1890, at the time of the Barings crisis, UK trusts held 36% of their assets in the US but by 1929, this had declined to just 7%. While the repatriation of capital to fund the UK war effort would have been a significant driver, one cannot ignore that UK (and Scottish investors in particular), did not get caught up in the late cycle euphoria so prevalent in the US in 1929. The reason for this in large part comes down to the lessons learned in previous bear markets and the investment values which characterise Edinburgh style: a focus on the long term, prudence, appropriate diversification while offering value for money to the investor of ‘moderate means’. The commitment to these values meant that UK trusts weathered the economic storm of the late 1920s and early 1930s far more effectively than their US peers.

1929 to 1967 – US Investment trusts decimated while UK trusts continue to grow

With the US Investment trust bubble being held partly accountable for the Great Crash of 1929 by US authorities, regulations tightened dramatically and the closed ended investment trust industry was largely replaced by the mutual fund structures we know today. By 1962, the US investment trust sector had just USD 1.8 billion in assets (compared to USD 7 billion in 1929!) while UK investment trust assets had grown to USD 2.75 billion by that time with 302 investment companies listed. The lessons learned and the values adhered to had stood the UK industry well. With Scotland continuing to gain market share, it can be no surprise that the lessons learned from the economic crises of the 1890s and 1930s have been so carefully handed down from generation to generation in Edinburgh in particular. Providing a long term store of value to investors of ‘moderate means’ while offering value for money in a sensibly diversified portfolio of international securities remains the hallmark of Edinburgh style today – just as it did so successfully in generations gone by.

Conclusion

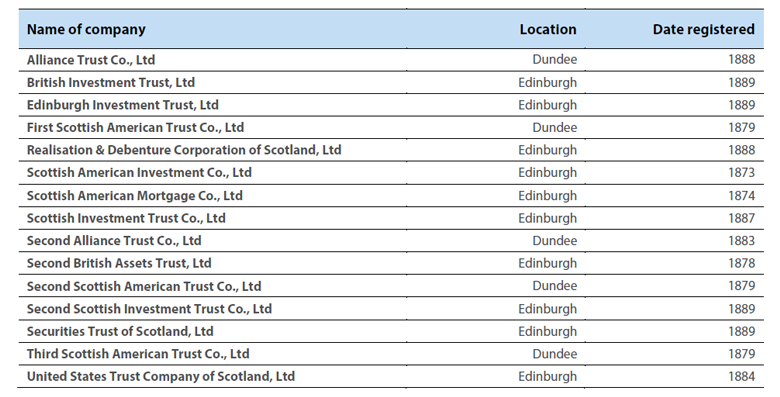

This paper has aimed to chart the origins of the investment trust industry in the UK and the significant role Scottish investors had to play as portfolio investment took off in the period after 1870. The trusts which established themselves before the Barings crisis of 1890 proved to be the most successful and heralded a rapid increase in market share for these Scottish businesses. Table 5 shows all of the Scottish Trusts incorporated in the period before 1890.

Table 5 Scottish Investment Trust Companies

Source: G. Glasgow, The Scottish Investment Trust Companies, pp. 38 – 70

The prominence of Edinburgh within this list is clear. Also, these trusts shared the values discussed in this paper; namely a prudent long-term approach giving appropriate diversification and value for money to the investor of ‘moderate’ means. Their enduring appeal and timeless values are proven by the fact that many of these institutions and funds are still in business today providing good value access to global equity markets for individual investors via regular savings schemes. Some are managed by asset managers in Edinburgh, such as Baillie Gifford, while others remain independent investment companies listed on the London Stock Exchange, such as Alliance Trust and the Scottish Investment Trust. This helps explain why Edinburgh has continued to be successful as a centre for fund management expertise.

Finally, it is worth noting that four of the five fund managers on the Edinburgh-based global equity team at Nikko AM started their careers managing money for these historic investment institutions. The fundamental values of prudence, long termism, appropriate diversification and value for money were passed on to the team by people who themselves were trained by the Edinburgh managers who performed so well in the Great Crash of 1929 and the subsequent depression of the 1930s. These values remain as relevant today as ever and our aim is to continue this legacy and ensure they are passed on to the generations that follow.