Australian RMBS provide a source of highly rated assets with consistent income generation. Two questions immediately come to mind when looking at them: how risky are they and how they should be priced? As will be discussed, RMBS are often maligned as being riskier than facts would suggest. On this basis, the second question becomes increasingly pertinent: are the spreads on RMBS attractive?

In Nikko AM’s view, Australian RMBS can be an attractive investment within portfolios. The caveat is that they can potentially be illiquid and tend to be better suited to portfolios that target longer investment terms and are not as focused on short-term trading.

An appropriate sizing of RMBS holdings within a portfolio can increase running yield while maintaining or improving overall credit quality of the portfolio. The structuring of the deals results in a variety of securities with different risk profiles from solid triple-A securities through to lowly rated or unrated deeply subordinated issues.

In order to consider the sizing and selection of issues, it is first essential to understand the structure of the RMBS issues under consideration and to validate that the securities truly merit the credit ratings they are assigned. Such analysis will also form a basis for comparison between issues – given the variations in structures and assets: not all RMBS are created equal.

Once the credit quality is understood, then the value proposition can be considered.

The credit quality of RMBS: more protection against house price falls than appears at first glance

In the process of understanding the credit quality of, there are three key points of distinctions between RMBS securities that need to be observed:

- Quality of the assets;

- Issue/issuer performance;

- Seniority of claim upon the assets.

Assessment of assets

There are a variety of aspects from which the quality of assets might be assessed. Some of the key areas of comparison include: the loan-to-value ratios (LVRs); loan terms; borrower income relative to mortgage payments; geographic distribution, borrower credit history; level of income verification; interest-only as opposed to amortising and owner-occupied as opposed to investment loans.

From the perspective of an investor in RMBS, the first focus is usually on the LVR since this represents the first level of protection on the mortgage: for example for a 70% LVR, house prices would need to fall 30% before the sale price of the property is less than the amount owing.

Other factors are, however, also significant and so Nikko AM’s initial analysis of an RMBS pool of mortgages focuses on finding concentrations of loans within a higher risk group, e.g. in an economically stressed part of the country.

Assessment of issuers/issues

RMBS issues can, in general, be classified as prime or non-conforming – prime loans in Australia have been defined as those qualifying for lender’s mortgage insurance (LMI). Usually losses on non-conforming loans are higher. The typical way to compare issuer’s performance is to examine the level of arrears and defaults on their mortgage pools, adjusting for whether the loans are prime or more aggressive. Some years back, an issuer presented to us claiming prime lending standards but showing non-conforming levels of arrears: the inability to marry the two statements led us to treat the issuer with great caution until later when their arrears reduced substantially.

Assessment of seniority of claim

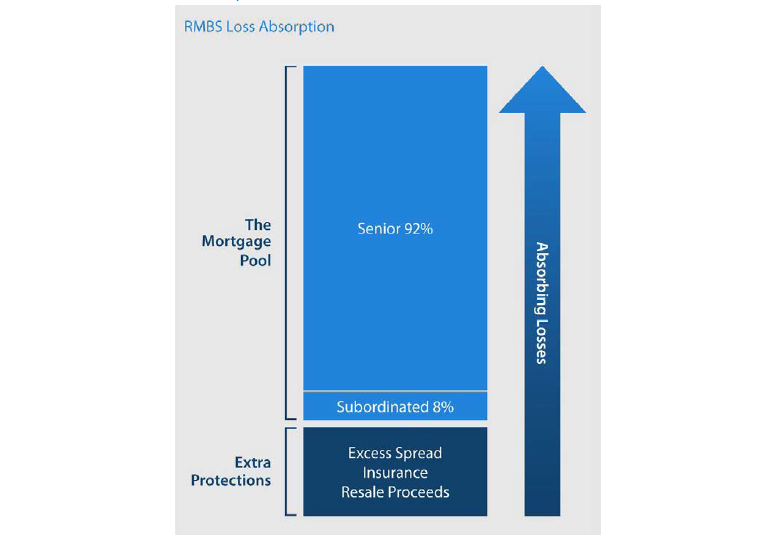

Seniority of claims is, however, the first and foremost part of assessing any RMBS issue and requires careful scrutiny. To understand this, a thorough understanding of the structure of an issue is necessary. We look at a simple (but common) example of structure here but in many cases, more complexities arise which will require a refinement of the process.

The example we consider is a Prime RMBS with a senior tranche consisting of 92% of the issue and an (unrated) 8% subordinated tranche.

The following diagram illustrates how losses are borne across the structure, if mortgages default.

- The property is taken into possession and resold – the proceeds are used to pay off as much of the mortgage as possible – including any interest on the loan that has accrued and other expenses;

- If there is a shortfall and there is mortgage insurance (in most cases loans with LVRs greater than 80% have LMI) then the shortfall is claimed against the insurance policy;

- If the LMI rejects part or all of the claim or there is no LMI, then excess spread is used to pay as much of the shortfall as possible (excess spread is the difference between the mortgage interest rate and the interest rate on the RMBS);

- If there is still a shortfall, then the loss is deducted first from the principal amount of the subordinated trance;

- Only once the principal of the subordinated tranche is completely depleted, will further shortfalls be charged off against the senior notes.

N.B. In step 1, a loss is only incurred if the property sale is at a price below that of the current amount owing on the mortgage plus related sale expenses and so the LVR of the mortgage provides a buffer against loss.

A further protection is that mortgages are personal liabilities in Australia and loss on sale may be recovered from the borrower, reducing loss to the RMBS securities. (Being a personal liability also reduces the incentive to “throw in the keys” if the property price drops below the amount owing on the mortgage – the borrower cannot just walk away unlike in many US states.)

Figure 1 RMBS loss absorption

Source: Nikko AM

As evidence of the extent to which the “extra protections” are effective, Standard & Poor’s recently stated that on all transactions that they currently rate, there were no write-offs against any tranche, including the unrated tranches i.e. all losses on sales have been covered by LMI or excess spread.

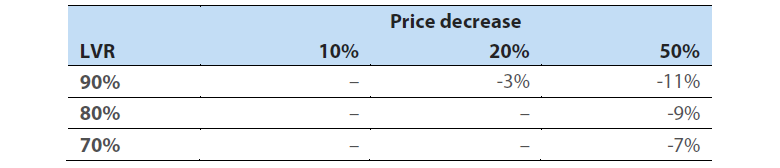

Even ignoring the extra protection, the probability of senior tranches being impacted is extremely low, as the following very simplistic conservative example demonstrates. In the example, it is assumed that a pool consists of mortgages all of a single LVR (90%, 80% or 70%) and a quarter of all the mortgages default (at once, before being paid down) without any benefit from the extra protections. Three levels of uniform house price falls are then considered.

Table 1 Percentage pool loss on mortgages if 25% default

Source: Nikko AM

So, if prices decrease 20% and all the loans were 90% LVR, then there is a loss of 3% of the pool value. Given that the senior bonds have subordination of 8%, they would incur no principal loss. In the table, a 50% decline for a pool of 80% LVR loans causes a slight loss. So the risk is if there are extreme decreases in prices on a very high LVR pool. It should be noted that rating agencies are well aware of this and would place much higher subordination requirements for triple-A issue if a pool had such high LVRs.

We see therefore that, while it is mathematically possible to create cases where a senior tranche suffers a loss, these cases are very extreme and suggest systemic failure within the economy: if one is to base decisions upon such cases then it would be prudent to invest only in government bonds and avoid financials completely - especially subordinated bank paper which would be very vulnerable to such a brutal housing market failure. (Nikko AM’s view is that such a scenario is extremely low probability and no investment thesis should be based upon it.)

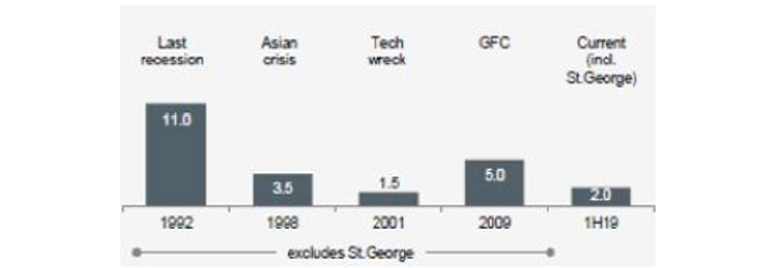

As a reality check on expected levels for loss rates at times of stress, in its latest result reporting, Westpac provided loss rates in terms of basis points over some major economic challenges over the past 30 years as shown in Chart 1. The worst case was Australia’s last recession and even that loss was only 11 basis points, which is less than a fifth of the typical excess spread on a deal for one year. Caution must be taken that mortgage pools may be skewed and other lenders may have higher risk but with loss rated at stressed times still remaining at such low levels, it is hard to see how losses on a prime pool could even impact the lowest rated tranches.

Chart 1 Mortgage loss rate

Source:Westpace

A further compelling reason to feel comfort with senior RMBS is to observe that in highly stressed times, senior RMBS in UK and Ireland did not default even during the worst of the financial crisis when house prices in these countries dropped by up to 50%.

Ratings on RMBS: reflecting reality?

As a final word on RMBS credit quality, an outstanding concern is whether the ratings are reasonable and useful. Given the rating agencies’ egregious errors on US subprime and CDOs leading up to the financial crisis in 2007, it is totally reasonable to question their structured finance ratings. However, their rating of Australian RMBS has not shown the same weaknesses and only the single-B or unrated tranches of non-conforming issues experienced any challenges at all during the financial crisis.

In response to the (justifiable) criticisms by investors and regulators, the rating agencies tightened their standards and have created more transparent and rigorous methodologies for rating RMBS, incorporating adjustments for the different factors that impact credit quality.

Rating agencies monitor deals and use the results to assess the effect of different factors such as LVR, geographic distribution, interest-only as opposed to amortising and owner-occupied as opposed to investment loans. These factors are then used to assess the amount of risks deals are carrying so as to set the level of subordination that is required. Even among prime deals the levels can vary substantially: in the current quarter prime deals had minimum subordination for triple-A rating ranging from 2.3% to 7.5% driven primarily by LVR levels but also by geographic and other compositional factors.

Following the improvement of rating agency analysis, given the earlier comments about the credit strength of RMBS, rating agencies seem to be providing reasonably consistent and meaningful ratings and analysis for RMBS. Accordingly, Nikko AM factors ratings into the evaluation of RMBS to be used in conjunction with Nikko AM’s own analysis.

Pricing and trading RMBS

Given Nikko AM’s belief that the credit quality of RMBS even down the capital structure, the remaining question is whether they are valued appropriately. On a basis of rating alone they would seem cheap: triple-A senior prime deals of about three years’ average life are currently pricing at over 100 basis points to swap compared to spreads for three year bank paper in the double-A rating band of nearer to 60 bps. As even more of a contrast, mezzanine triple-A assets can be priced up to 200 basis points over swap. Single-A five year tranches can price near to 300 basis points over – more comparable to double-B rated bank loans.

However, it is not as simple as comparing these spreads. Those who held RMBS in 2007 – 2009 during the financial crisis know how the prices of RMBS can suffer – in some cases triple-A senior RMBS were discounted by as much as 20% even while the pools themselves were performing quite satisfactorily.

In this case, margins on RMBS had tightened too much. The margins on a senior deals were issued as low as 13 bps above swap and 5-year mezzanine tranches as low as 16 basis points. At these levels they were highly sensitive to any negative events and when the financial crisis hit, they suffered. This irrational pricing highlights the fact that RMBS, like any other investment, can be mispriced and there are times they should be avoided.

The reason for this irrational pricing is in itself revealing: these triple-A assets were bought by leveraged investors as being completely safe. When the leverage in the system was throttled by tightened standards, the leveraged holders became forced sellers at a time when buyers were few and far between. RMBS were not credit impaired unlike many other parts of their portfolios and so could be sold but only at very unattractive prices. So, in this case, it was an extreme supply-demand imbalance that drove prices down not credit concerns.

At the time when forced sellers were flooding the market with supply, other holders were exceedingly unwilling to sell their paper. As the market settled and the flood of paper dried up, the difference between where holders were willing to sell and what buyers would pay was more than for many other asset classes. Even today the bid-offer spread on RMBS can be a discouragement for trading.

Another point to bear in mind is that RMBS pricing is more complicated both from the logistics of managing monthly prepayments and from the evaluation of what is the actual margin of a security if it is priced away from par – the margin is sensitive to prepayment speed assumptions (although this sensitivity is negligible compared to that of US fixed rate RMBS).

The net result of the wider bid-offer spreads and the relative complexity to trade is that RMBS need to have an added “illiquidity” premium to the spread at which they trade. How much this premium should be depends on the investor’s viewpoint: for those with short investment time horizons, the premium being offered by RMBS may seem inadequate but over a medium to long time horizon, the current premium seems attractive.

In the last ten years since the financial crisis Australian RMBS spreads have been considerably wider than at any time leading up to 2007. As a general rule the range of 90 to 120 basis points spread for a major bank senior tranche seems to be the standard with other issues being priced at pick-ups above these benchmark issues. When margins fall below 90, support for deals from investors has been reduced while at over 120, bank issuers tend to focus more on alternative funding strategies. Within this range, RMBS would seem an attractive investment. The increased number of participants in the Australian RMBS market may squeeze the margins, particularly at the wider end.

RMBS are, however, poorly-suited to trading strategies such as taking views on their spreads since their non-standard issue structures, bid-offer spreads and uncertainty due to monthly prepayment could erode the performance of any view-taking position.

Issues other than prime senior tranches

Much of the discussion has been focused on prime senior issues. Given they form by far the majority of issuance, this focus is reasonable. The arguments that suggest the prime senior market offers value to longer-term investors can be re-calibrated to the subordinated tranches to reveal that, given their margins are substantially wider, they also seem attractive for those with a higher risk tolerance.

As for non-conforming issues, the fact that they are treated more severely by rating agencies means they have substantially higher subordination levels, which coupled with higher margins means they also can be attractive investment – in fact, the increase in subordination may even make their senior tranches stronger than those of prime issuers.

Conclusion

As discussed, RMBS are best suited when a longer holding period is considered. Their monthly pass-throughs and resulting uncertain amortisation create (by no means insurmountable) complexity for secondary market trading. However, the key take-away should be that RMBS provide attractive spreads with solid credit profiles which are less exposed to house prices than some commentators imply.