One of the most frequent questions that we are asked revolves around whether we are headed for another Global Financial Crisis – or perhaps even ‘Part Two’ of the last one….. It is firmly our view that crises rarely occur because of something that the ‘markets’ know about, instead they tend to be the result of exogenous news or processes that the markets were previously unaware existed. The original GFC is of course an example of the latter; there were a (small) number of analysts that were aware of the true extent of the US Mortgage Boom and the Global Credit Boom (particularly those of us that were working with the major investment banks at the time) but the mainstream commentary had little idea about the true multi-trillion-dollar scale of the US mortgage boom that occurred in the mid-2000s, or its incredibly shaky mathematical foundations. Arguably, it was the latter that triggered the GFC – the credit boom created the potential for a Crash but it was the boffins working within the Compliance Departments of one or two of the major investment banks that actually “pulled the plug” on the cycle. This is of course why the GFC came as such a shock to so many – it occurred in the ‘shadows’ of the credit system and as a result was largely under-recorded in the conventional data and its very existence required on some rather stretched technical assumptions within matrix algebra…..

Unfortunately, we do sense that in many ways history has indeed been repeating itself once again. Indeed, there has been yet another major credit boom occurring and it too has owed much of its existence to high-powered maths and some potentially dubious assumptions. Hence, to answer our own question, there is indeed the potential for a new crisis and we believe that if it does occur - and it is by no means certain that it will occur – then it will have its centre within China’s economy.

It is now a matter of record that China has experienced one of the largest (or the largest?) credit booms in financial history between late 2016 and mid-2018. According to the official data, that almost certainly understates the truth, China’s banks added around $6-7 trillion of domestic credit during this period and a further $3 trillion of lending offshore, typically to Low Income Countries (LIC) in Africa and the Pacific Region (although they were also active in parts of Eastern & Southern Europe). On top of these reasonably transparent bank flows, there were also heavy levels of bond issuance and it is our sense that, between 2015 and today, China has added the equivalent of around $15 trillion to its stock of total debt in exchange for a $2.5 trillion increase in the country’s aggregate GDP (a number that itself may have been overstated). We firmly believe that the Great China Credit Boom (GCCB) will one day take its place in the financial history books…

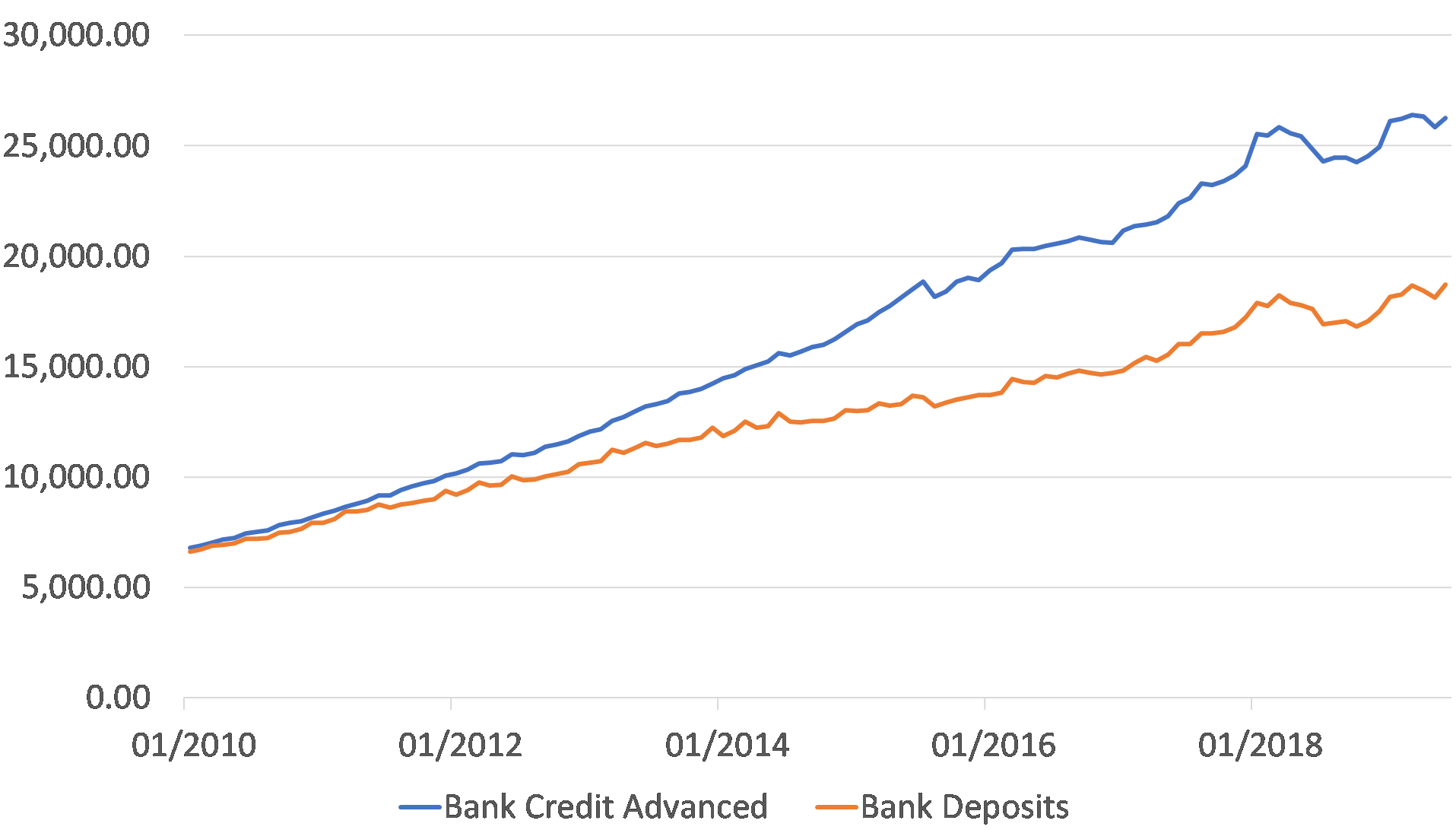

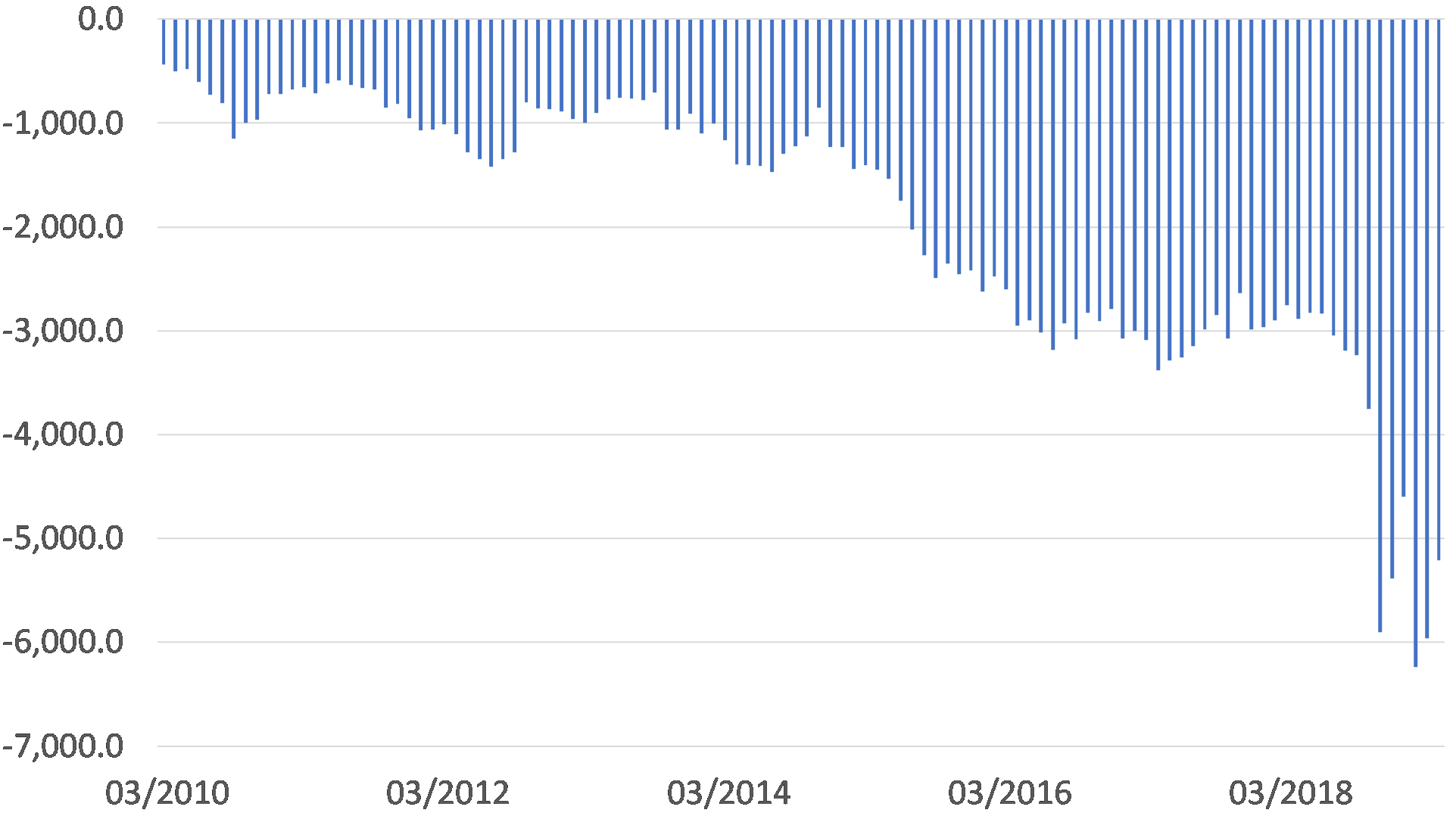

Crucially, if somewhat technically, we find that the $6-7 trillion increase in bank lending was only partially matched by a $3.5 trillion increase in the system’s domestic deposit base. As a result, the Chinese banking system in aggregate now possesses a loan to deposit ratio of around 130%, which is high by global standards and tells us that half of the increase in bank lending that occurred since 2015 was financed from non-deposit sources. Some of this ‘opaque’ funding was provided by direct loans from the PBoC, and there was clearly also some funding from the bond markets / Wealth Management Product sectors, but it is our sense that around two thirds of the non-deposit financing that was utilized by the banks during their recent lending bonanza came from foreign currency denominated sources. Some of these ‘foreign sources’ took the form of transparent deposits and other conventional instruments but both the data and sources suggest that the bulk of the necessary funds that were raised came through ‘clever offshore structures’ and that much of the lending occurred via the opaque, heavily leveraged, exchange-traded-derivative markets and other routes that relied on clever maths and a degree of ‘myopia’ by the regulators. This of course all sounds rather too familiar…..

When we have in the past attempted to construct what is known as a ‘monetary counterparts’ for China, and through this exercise we concluded that China’s banks currently possess foreign liabilities of circa $2.5 trillion (+/- $250 billion). Separately, an analysis of China’s balance of payments data has suggested a similar amount. We are, however, aware that at least one analyst using micro data has estimated that the banks possess foreign liabilities of around $4 trillion but we suspect that there is some double counting in these estimates.

China: Bank Loans and Deposits

USD billion levels

The high (approximately 30%) share of foreign financing of the banks’ asset growth since 2015 bears unfortunate comparison with practices utilized by Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Korea in the mid-1990s, the Czech Republic a little later, and Turkey more recently (note that this does NOT imply that China will necessarily share the same fate – see on).

We are aware that the rapid slowdown in China’s domestic credit data in 2018H2 was in fact caused by a drying up in the supply of foreign funding. When we initially espoused this explanation for the slowdown in China’s credit data towards the end of last year, it was in general greeted with some incredulity but over recent months the view has become somewhat easier to present and we are aware that a number of central banks and official bodies are looking closely into the situation for themselves.

What is also all too clear is that, as the ‘run rate’ for credit growth dipped below that amount that was necessary to fund the SOE, private sector and Local Government operating funding gaps, China’s economy was forced to slow sharply. Indeed, we believe that China experienced a full-blown manufacturing sector recession and a CAPEX recession in late 2018 as a result of the credit constraints that were explicitly caused by the drying up in foreign funding. The authorities may have been following a ‘de-leveraging agenda’ but the severity of the squeeze was imposed by external forces surrounding the availability of ‘wholesale dollar funding’.

During the second quarter of this year, however, it became apparent that the authorities in the PRC were reacting to the weaker economic situation. There was a modest easing of credit conditions over the course of the second quarter, and a more determined easing of fiscal policy. Interestingly, neither of these policies seem to have been maintained over recent weeks, with the result that the monetary base is now falling once again and the fiscal deficit has shrunk quite significantly on a sequential basis over the last month or two.

China: Monetary Base %YoY

China: Budget Balance

RMB billion over 12 months

The Mid Year ‘Bounce’

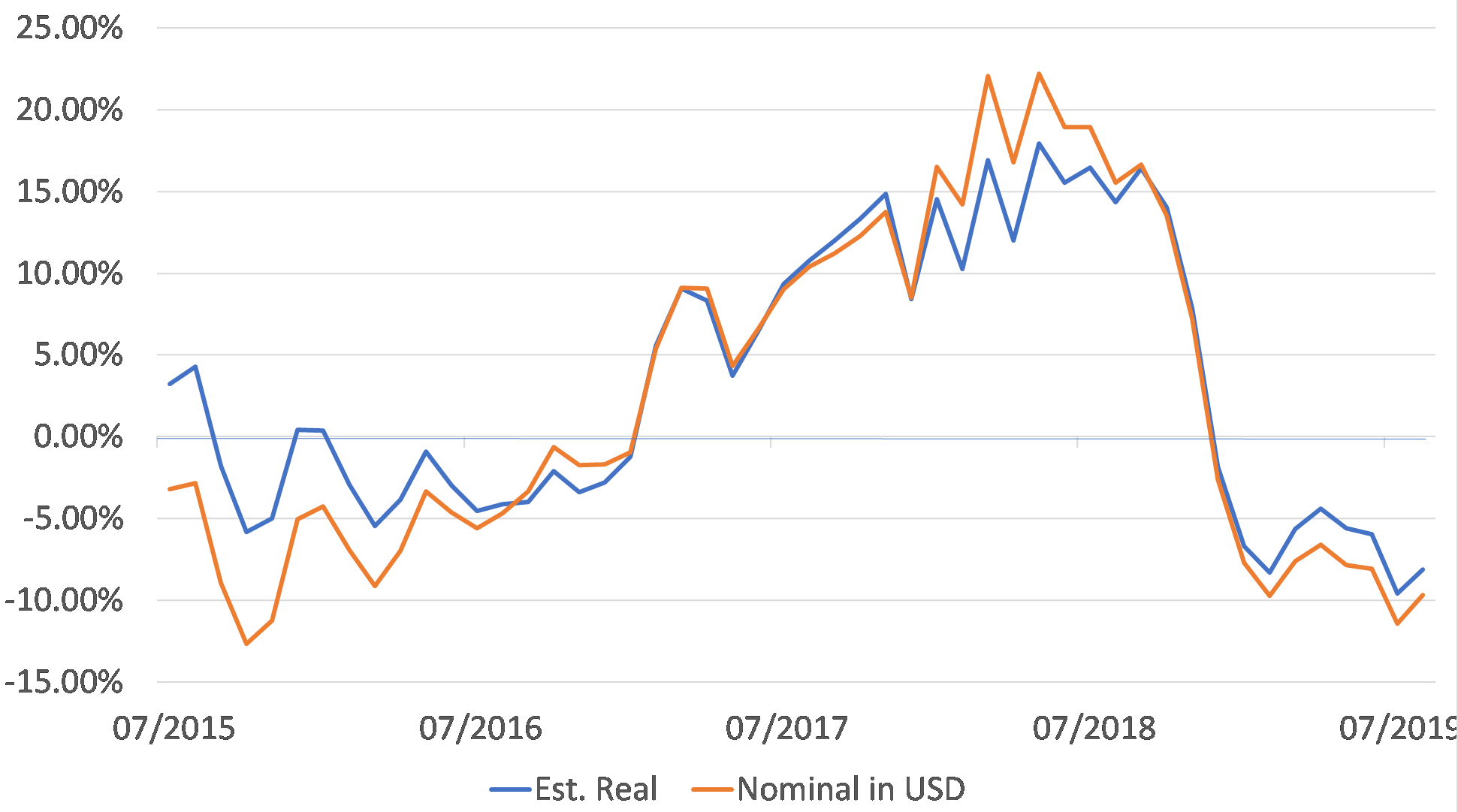

The authorities’ actions over the second quarter were certainly effective in generating what in effect amounted to a ‘mini-bounce in the economy. In particular, we note that the recession in the industrial sector eased and there has even been a modest recovery in the level of the data. Moreover, the import volume data also improved, and this provided a seemingly welcome if modest boost to global trade and growth trends almost world-wide. This was in turn reflected in the behaviour of global financial markets.

The question that of course arises from this situation is why did China not continue ‘pressing the accelerator’ and continue with its easing stance? Clearly, policy has tightened quite sharply over recent weeks (see the previous charts) and there are signs that the tightening is already negatively impacting both domestic and global economic growth trends.

A Familiar Constraint

It is our firm belief that the abrupt ‘policy abort’ was caused by the pressure that arose on the RMB and to an extent the HKD. As domestic liquidity conditions improved, it seems that China’s banks quite naturally began to discharge their now quite expensive foreign liabilities. Certainly, there was a reported decline in the official (inaccurate) measure of the banking system’s external liabilities but more tellingly data from the creditor countries and their banks, together with data from the Chinese banks themselves, appears to confirm that a large proportion of the funds that were added to the economy by the authorities were ultimately used by the banks to discharge some of their foreign liabilities. Hence, the loan to deposit ratios of the banking system began to improve at the margin.

The (Global) September Relapse

While this situation undoubtedly represented good news for the individual commercial banks that were being allowed to reduce their now expensive USD liabilities, the situation was much less positive for the currency and the PBoC. We believe that it was these pressures that forced the policy ‘U-turn’ and that, had the authorities continued to ease, then they could have risked creating a re-run of the Asian Financial Crisis as the banks each attempted to repay all of their foreign liabilities before the RMB fell. The resulting $2 trillion or more of outflows would have caused a sharp decline in the RMB and a resulting collapse in bank capital as the domestic value of the Foreign Liabilities soared.

We personally have witnessed such a dynamic take hold in numerous countries over the last 30 years and we suspect that China had no desire whatsoever to follow this now familiar narrative. Hence, the policy easing of 2019Q2 was aborted in order to protect the RMB and the FOREX reserves. Naturally, as policy tightened and demand levels in China slackened, the economy’s import trends suffered a relapse that has since been reflected in a host of weak economic data around the world over recent days.

China: Non Oil / Non Commodity Imports

% YoY, 3mma

But Why No Crisis; It is Different This Time

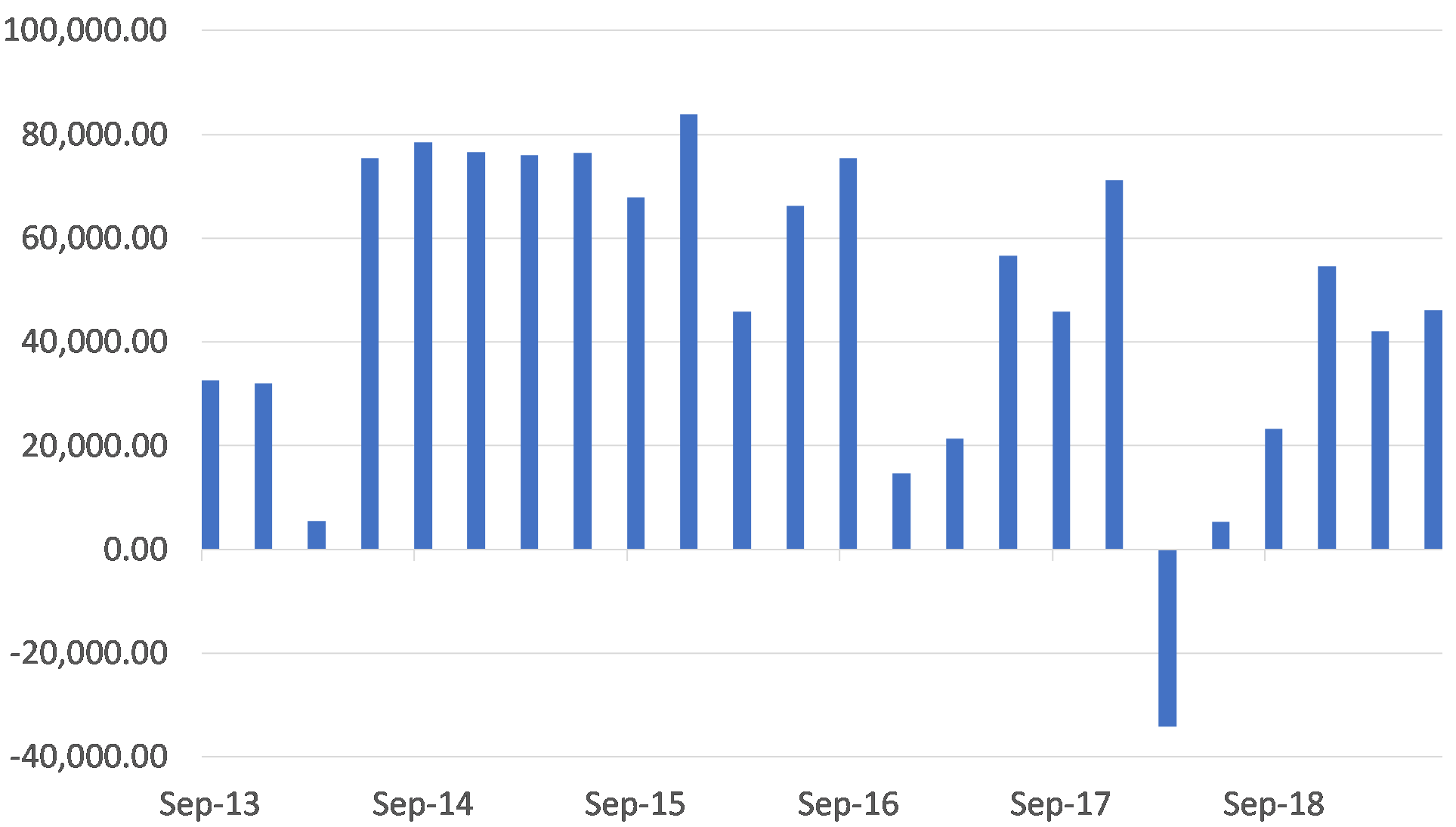

We firmly believe that, if China possessed a current account deficit at present, then we suspect that both China and the World would by now be facing the reality of a new Asian Financial Crisis style event in the World’s second largest economy. Such na event might easily trigger a new GFC that might engulf as all.

However, the fact that China has a current account surplus (that has so far provided it with a steady source of dollars) as well as a stock of liquid foreign assets (such as deposits in US and Australian banks) that it has been able to sell, has allowed the country to so far ‘escape’ such a dramatic fate.

During 1997, all of the Asian economies possessed current account deficits and large basic balance deficits; China at present has a current account surplus and only a small / intermittent basic balance deficit that has thereby allowed the country to service its debts without recourse to ‘printing domestic money for the banks’, and thereby collapsing the currency in the way that the BoT and others were obliged to do. Naturally, the fact that China has avoided such a crisis has helped to support financial markets globally.

China: Current Account Balance

USD million quarterly

In practice, China’s mix of a current account surplus, its ongoing courting of foreign bond investors (via its inclusion in the global indices), and of course its own capital accounts have, along with a degree of implicit FOREX intervention, created a sufficiently large supply of dollars to allow its domestic banks to service their liabilities without there being ‘an event’, so far…….

But Further to Go

Unfortunately, the fact that China has avoided a crisis over the last year does not mean that the country is ‘out of the woods’. There are still $1.5-2 trillion of foreign liabilities that need to be serviced and hence we can assume that China’s demand for dollars will remain elevated for several years. Therefore, the authorities will wish to continue to attract foreign portfolio flows (including via Hong Kong) wherever possible, but more importantly the country will need to maintain its current account surplus over the medium term, even in the face of a trade war.

In order to maintain its current account surplus against the background of weak global growth, China will need to ensure that its rates of import growth remain weak / negative and that the recent growth in outward tourism is curtailed.

Of course, any diminishing in China’s demand for imports and reduction in its tourism flows will help to perpetuate the current weak Global Growth environment. China’s requirement to run large current account surpluses for the next few years (just as Greece is being obliged to do so that it too can service its debts) will imply sustained weak rates of import growth. However, Greece, unlike China, is not the world’s second largest economy….. China’s growth constraints, if they are adhered to, will be felt by all of us if they are allowed to persist.

The Future: GFC Risks and Opportunities

Our base case (50-60% probability) remains that China implicitly adheres to its growth constraints, import growth remains weak, and that the RMB only weakens slowly as the country takes 3 – 5 years to recycle its current account surpluses into debt repayments. This would of course represent a relatively long period of global stagnation and attendant ‘deflation risks’ but markets would presumably be spared any immediate China Crisis and they would from time to time be supported by G3 policy responses. In time, the FOMC probably would introduce QE4 under these circumstances and the low growth / low rates / hunt for yield dynamics that we have grown accustomed to would presumably continue, even as global earnings growth stagnated and populations (presumably including in China?) became restless. Support for this hypothesis can be found in the fact that China’s trade surplus has if anything been increasing over recent months, which does suggest that the strategy could work in theory at least.

Perhaps a more optimistic-still outcome would be that, for whatever reason, the Federal Reserve, BoJ and others decide to flood the world’s money markets with cheap financing through large scale QE’s and that, far from needing to reduce its foreign liabilities, China’s banks find that they can increase them yet further and begin a new instalment in the Great China Credit Boom.

Such an outcome might not suit the US’s political agenda but a sustained easing of G3 policy that was transmitted through the money markets to China could allow a ‘1995-6 effect’ within China. The Asian Financial Crisis had what amounted to a false start in 1994 – the crisis was certainly beginning to take shape in 1994 as the FOMC tightened but the Mexican Crisis in effect occurred first and so caused the Fed to reverse its stance and ease for a further 18 months, with the result that the Asian Crisis was delayed for two years – although by the time that it did burst the underlying problems had become even more severe in the intervening period.

It is certainly possible (10%-20% probability) that the current round of easing by the FOMC could provide the PRC with a reprieve in the near term and create a new leg to the boom rather than a crisis.

The final possible outcome centres around the actions of the ‘risk police’ operating within major US banks, which are in effect oligopolies within the wholesale funding markets. It is our sense that a mixture of regulatory and perhaps even political pressures, coupled with a degree of sober analysis of their existing exposures, as well as the near term pressures on funding markets caused by the US Treasury’s heavy issuance calendar and the loss of foreign central bank dollar deposits, is currently causing a decline in the availability of wholesale dollar funding to non-resident financial institutions despite the FOMC’s promises of further rate cuts and continued liquidity injections.

It is entirely possible (a 20-30% probability?) that the credit crunch that last year continues to build momentum to the point at which it may come to exceed the PRC’s ability to reduce its foreign liabilities by recycling its current account surpluses. Clearly, if the potential supply of dollars to China falls by more than China can reduce its level of demand, then the PRC will find itself placed into a similar situation as Korea et al in 1997. At this point, China would have no option but to begin printing money, collapse its currency (with intense deflationary consequences for the world) and perhaps even experience some form of Financial Crisis of its own which could indeed soon ‘infect’ the global system. As we suggested at the outset, there is certainly a potential for a new GFC, and this is in our view the most likely route by which it might occur.

In effect, the difference between the 60% ‘muddle through / sustained weak growth / no crisis scenario, and the 30% crisis scenario, will be defined by the speed that China’s banks can reduce their foreign liabilities relative to the speed at which the US lenders wish to be paid back against the background of a FED easing. If the US banks require an aggressive repayment, a crisis will most likely occur but if the US banks are generous, or indeed encouraged to be generous by an active Fed, then the non-crisis scenario will most likely prevail.

Conclusion: Collusion or Self Interest in New York?

On a practical level, if the US lenders and central banks were to collude, and thereby agree not require a rapid repayment of their debts, then it is probable that a full-blown China crisis could be avoided quite easily. However, there is also a classic prisoners’ dilemma situation at world here; if the banks either do not collude, or simply do not trust each other to abide by any agreements, and instead attempt to use the other parties’ largesse to fund their own escape from their own exposures, then a crisis is the most likely outcome. Clearly, the world is in an ‘interesting position’ at this point and we would suggest that the obvious signs that things might be about to go wrong would be:

Heavy net T bond issuance that causes further instability in the funding markets despite the Fed’s actions;

Ongoing weakness in the US intra financial system credit data referenced above – this is clearly a ‘live topic’ at present;

Any weakness in China’s current account data.

If any or all of these features emerge, we would argue that investors should adopt a suitably more risk off stance but if these warning signs are not illuminated, we may simply be back to a ‘lower for longer’ scenario that has become so beloved by the markets.