Financial markets have been in the grip of a liquidity boom for much of this year. In fact, the process began in the closing days of 2018, when Chairman Powell at the Federal Reserve made his hurried and very public ‘U-turn’ in Fed policy in response to the global economic slowdown and reports that pressures were building in the USD funding markets as the year-end approached.

The predictable impact of the Fed’s “tightening on hold” statement was then amplified by the reaction of the US corporate sector to the results of the Mid-term elections, and perceived increase in the threat of an impeachment of the President. When the outlook for the Trump presidency appeared to deteriorate, there was a rush of corporate repatriations of profits formally held abroad that lifted the amount of liquidity in the US banking system by more than $200 billion in January 2019 alone.

These corporate flows were however waning by February but at this point issues with the US Debt Ceiling required that, between late February and August 2019, the Treasury was obliged to reduce its cash balances at the NY Federal Reserve by $240 billion. In effect, the government was spending much more money than it was receiving in either tax receipts or through its bond issuance, so substantial amounts of liquidity were thereby injected into the financial system.

Indeed, if we aggregate the impact of the corporate repatriations and the reduction in the Treasury’s General Account on the monetary base, then we find that there was a net injection of almost $500 billion in the US monetary base over the course of the first seven to eight months of the year. Crucially, the implied monthly ‘run rate’ was as large or at times larger than during any of the Fed’s QEP experiments earlier in the decade.

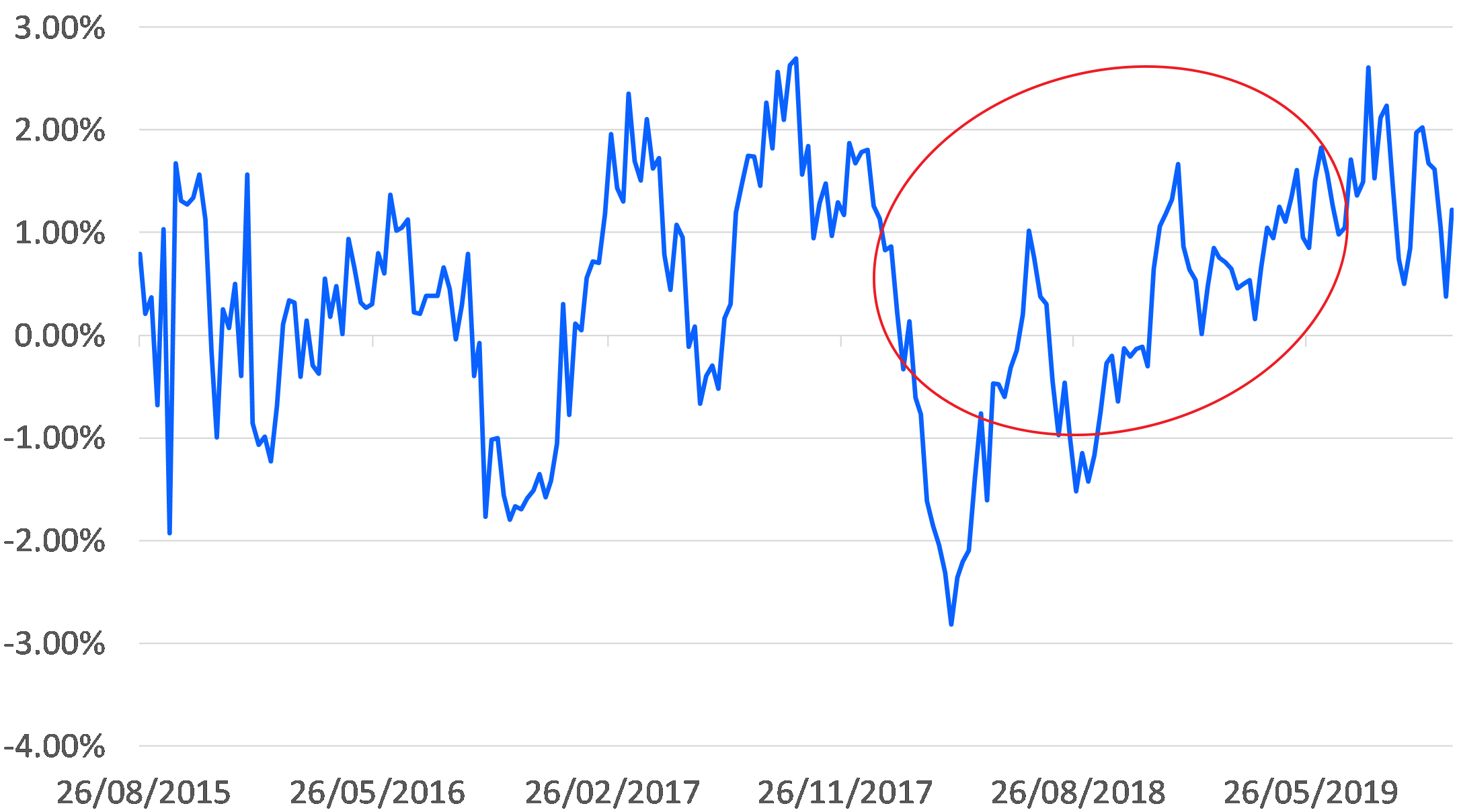

Admittedly, the US banks may not have been quite as ‘gung-ho’ with regard to using this liquidity as they were in 2017 but, nevertheless, there was still a surge in bank lending to other financials (including foreign banks and leveraged investors) that will have benefited the financial markets.

USA: Bank lending to financial sector and securities market

% 3 month

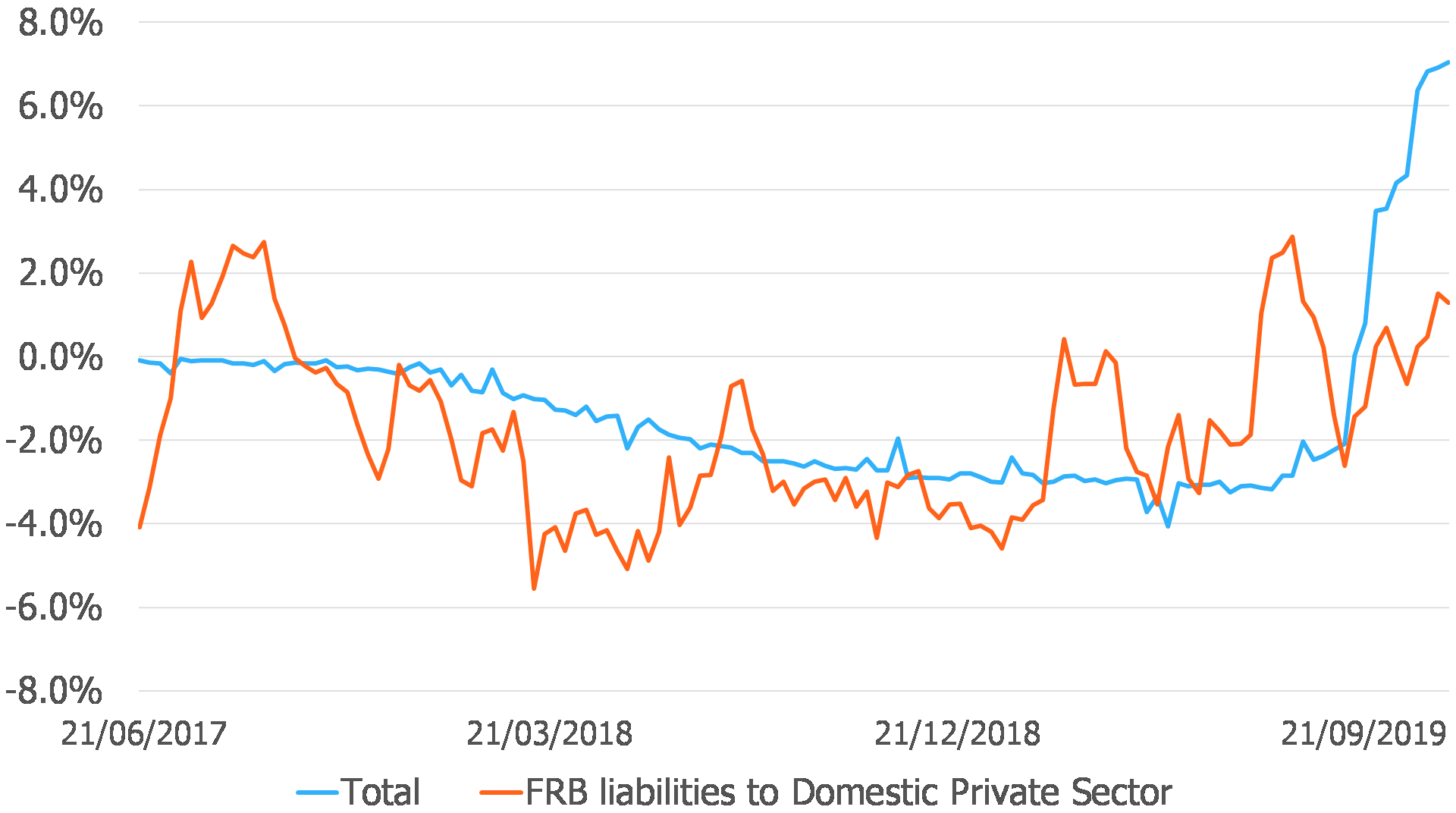

Crucially, these two rather abnormal flows had either ebbed away (the repatriations), or even reversed in the case of the Treasury by September. Indeed, during September, the Treasury issued particularly heavy levels of debt securities as it began to rapidly rebuild its own cash balances. In fact, by the end of September, the Treasury’s actions were causing the US monetary base to shrink at a double-digit annualized rate and, in an unfortunate coincidence, the timing of this event coincided with not just a surge in demand for dollars from China’s hard-pressed banks but also a regulator-driven tightening within some of the European countries and in Japan (there is a seasonality to bank asset growth, and September is usually a weak month due to the Japanese ‘half fiscal year’ and the end of quarter effect within the EZ). We therefore witnessed something of a ‘perfect storm’ for USD, which was in turn reflected in the ‘spike’ in USD funding costs late in the month.

It is clear that the Federal Reserve was in effect ‘spooked’ by this spike in rates and its reaction was notably ‘enthusiastic’. Indeed, since the event we have witnessed a sharp increase in Fed’s provision of repo lending and new asset purchases (which whether called QE / Monetization / MMT or not, do nevertheless imply that the Federal Reserve has been creating the money that has been used to fund at least some of the budget deficit and therefore been given to the real economy when the government has spent money…), and there has also been something of a ‘love-in’ between the central bank and the commercial banks.

To re-use a certain phrase, Powell has it seems been promising that the Fed will do whatever it takes to stabilize short term rates and to ease funding pressures within the dollar markets. The Fed has not just been providing funds to the banks, it has also been providing a ‘time commitment’ over the likely duration of its policies.

USA: FRB balance sheet

% 13 weeks not annualised

The situation has been a little more complex in Europe this year. Almost ironically, liquidity growth within the EZ was relatively strong over the middle part of the year as companies were obliged to borrow more in order to finance their surging levels of inventories and, at the same time, the global economic slowdown encouraged the European banks to re-enter the domestic bond markets as buyers rather than sellers. Clearly, the result of both these factors was a marked pick up in overall liquidity trends, despite (or perhaps because of) the higher yields in the early part of the year. However, over recent weeks, the corporate sector appears to have moved towards a de-stocking phase and rumours (in our view unfounded) of an imminent global recovery have led the banks to become heavy sellers of bonds even as the ECB has mounted a rather ‘half-hearted’ easing. Therefore, although the ECB has returned to a QEP, monetary conditions within the Euro Zone have tightened at the margin over the last month or two (albeit from a relatively high base).

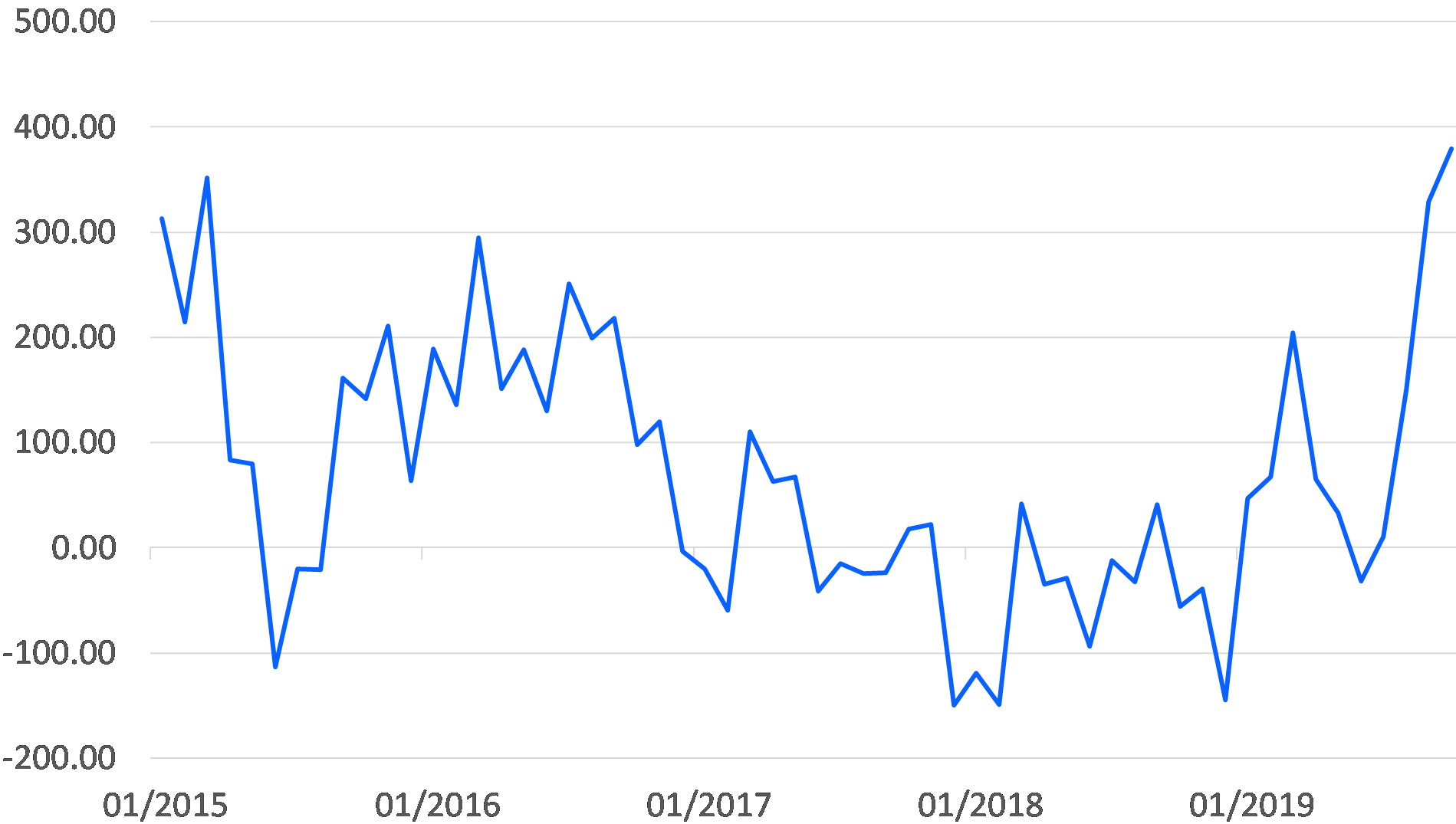

At present, it is our sense that the Fed’s actions are dominating and we can observe that, if we look at the total level of net bond purchases by the ‘G3’ banking systems, then we find that we are witnessing rates of debt monetization that have not been witnessed since 2016 or arguably the tail end of QEP3.

G3 Bank purchases of debt securities

USD billion current dollars

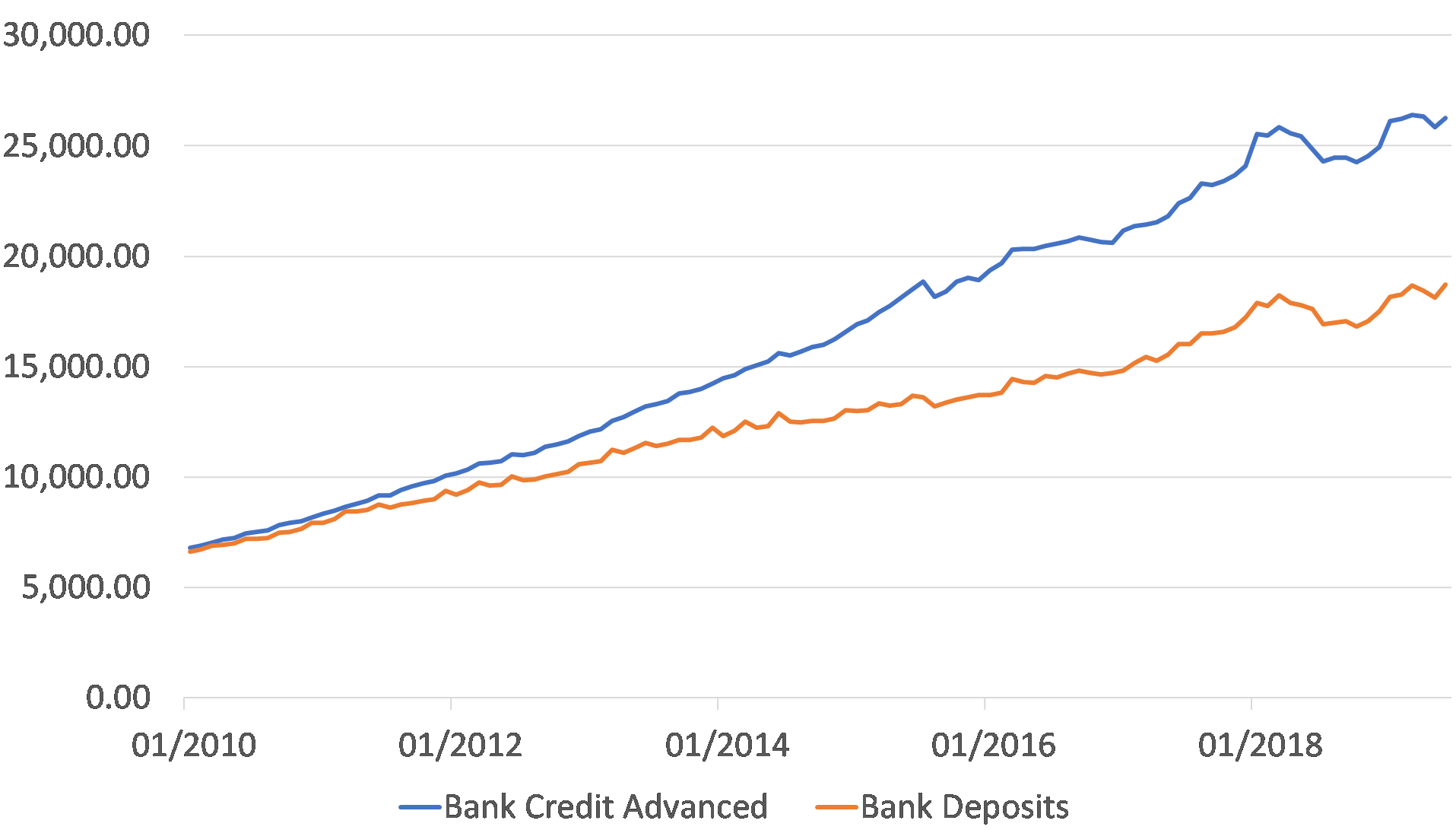

In fact, given just how many bonds the central banks are in effect taking out of the system at present, it is in no way surprising that investors are gaining high cash balances that they probably need to deploy, and that there is ample funding available for the high levels of corporate bond issuance that are necessary to fund the all important equity buybacks in the USA. Certainly, we believe that it has been the buybacks rather than the corporate sector’s profit performance that has supported equity valuations of late.

USA: Corporate Zaitech

USD billion change in profils, quarterly borrowing and equity buy-backssaar

In a practical sense, capital markets are no longer providing capital to corporates so that they can invest in real facilities and equipment and instead the financial system seems to have morphed almost solely into marketplaces in which people trade pieces of paper in the hope of selling them for a higher price than they paid for them. In such a world, liquidity and ‘rumour’ (i.e. real news or fake news) have become kings and most attempts at fundamental analysis have become temporarily redundant. The origins of this year’s liquidity boom may have been unusual, desperate, and even a little ‘random’ but there can be no doubting that we are in a liquidity boom and that markets are currently enjoying the experience.

Perhaps the one surprise within the current dollar-based liquidity boom has been that the USD itself has not been weaker, and that the Emerging Markets have not in fact performed better. Normally, when USD liquidity is surging the EM tend to produce high absolute and relative returns but the fact that this has not happened tells us something about their situation and in particular just how short of dollars they are now that they have amassed a substantially larger stock of USD-denominated debt and suffered from the effects of the slowdown in global trade. The latter has, of course, limited their access to the dollars that they might usually earn via their exports.

The relative failure of the EM to react to the dollar boom also hints at there being a number of risk factors to the current asset price ‘melt up’ in the Developed World. Firstly, there is a significant risk that a corporate or financial entity or country simply defaults on some of its debt or ‘goes bust’. There may well be further ‘Argentinas out there’ and we certainly fear for the outlook for parts of Africa, the Pacific Islands, and some of the China-related entities that have over-borrowed since 2015.

Secondly, even if none of these entities actually goes bust, they will likely still have an immense demand for dollars. It is not impossible that, despite the surging supply of dollars onshore in the USA, there is a shortage of dollars offshore as 2019 draws to a close. We may well see upward pressure on the dollar and offshore funding costs over the coming months.

The other significant risk factor that could potentially curtail the current boom would be a decline in the money multiplier caused by the impact of the regulators. With most of the major banks in breach of their GSIB rules and the EZ banks in particular under legal pressure to shrink their balance sheets into year end, we could find that although the central bank money printing engines may be in full-swing, the transmission mechanisms in the form of the banks may be compromised. Indeed, we wonder whether some of the recent week-to-week volatility within the data for US bank lending to other fincos has been caused by the tug-of-war created between the Federal Reserve’s overt efforts to boost bank asset growth, and the regulators’ efforts to shrink the banks’ balance sheets in pursuit of longer term (global) financial stability.

In theory, the central banks could re-route their stimulus away from the ‘commercial bank transmission route; by using more direct forms of explicit QE rather than repo-type facilities but such initiatives can take time to enact and it would also place the FOMC in a difficult situation, since for the Fed to re-introduce an overt QEP at a time in which the US economy is still fully employed and domestic inflation rates have not fallen back (in fact, they are still at the same level that they were occupying when the Fed was tightening during 2018) would imply that the Fed was once again taking on the responsibility of being the global central bank. Given the Fed’s apparent commitment to defend asset prices come what may, the Fed probably would act but it is by no means certain that it would act pre-emptively.

At present, there is undoubtedly enough (predominantly USD) liquidity and suitable ‘rumours’ (i.e. of a global recovery) to justify a further speculative melt-up in markets in the near term but we would urge that investors take a more cautious approach into year end when the ability of the Fed to maintain the current liquidity cycle will be tested. The 2019 liquidity boom was founded on a number of unusual and in many cases essentially one-off factors and it is not clear that the cycle can and will be extended into 2020. At the risk of sounding like the two-handed economist, the liquidity cycle could be sustained into 2020 but such an outcome is not guaranteed and in any case ‘seasonality’ may be against us from mid-December onwards.