Late last year, Japan’s parliament passed an amendment to the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (FEFTA) that will tighten the rules in May for foreign investors seeking to invest in companies related to Japan’s national security. Although all the details have yet to be finalised, certain foreign investors will be required to notify the government and receive prior approval if they want to purchase more than 1% of a designated company’s outstanding shares, down from the current threshold of 10%.

This has been a source of concern for many investors, especially as initially, the details of its implementation were vague. However, the government bodies responsible for such, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry have responded positively to these concerns and have made it very clear that there is no attempt to reduce the activity of foreign investors except in very clear cases of national security. Indeed, their tone has been to encourage foreign investors and to continue supporting shareholder activism. They now have clarified that any foreign investment management company regulated by a major national supervisory agency, such as those in the US, Europe, or the equivalent of such, will be completely exempt. Similar such banks, insurance companies and even regulated high frequency traders will also be exempt.

Moreover, initial concerns that foreign investment managers would not be able to pressure managements to reform their operations of national security related companies have been alleviated by the now clear intent to regulate only the nomination of themselves or closely related persons to the board of directors and regarding the disposition of key divisions. Access of non-publicised national security related information is also prohibited. Even for those foreign managers that are not exempt will only be required to file a simple form and should expect a decision within five business days.

As for foreign managers that might not be automatically exempt, sovereign wealth funds and foreign public pension funds will need to prove that their investment decisions are independent from their governments or have exempted asset managers (including local firms) independently vote their shares for them. Foreign foundations will also need to have exempted asset managers independently vote for them. Lastly, select pension funds and endowments may even be granted full exemptions.

A list of national security related companies will be published in the coming months, with the expectation that it will be rather short, but will very likely include public utilities. Several of these are such large companies that very few foreign asset managers would likely push above the 1% notification threshold, if they were not exempted anyway.

This new development is unfortunate in many ways, but the world has changed in recent years and many countries are adopting national security rules, often with the encouragement of the US national security agencies. Fortunately, although there was some initial major investor concern about this new law, the implementation looks to be rather mild and only applied in in extreme cases. It is also noteworthy that the relevant national security regulations in the US are much less clear than Japan’s and give regulators wide discretion on implementation. National security regulation in many other countries are often subject to rather arbitrary decisions, as well.

In sum, the ability of foreign investors to influence Japanese companies remains very strong except in a few very clear exceptions.

Also it is crucial to realise that Japanese investors, both institutional and the more activist type of investors, are fully dedicated to pressuring corporations to improve corporate governance (see the excerpt from our 2020 Japanese Equity Outlook). Thus, the FEFTA uncertainty factor will likely decline fairly soon, although there will always be a few dissatisfied or jaded investors, so the number of investors using this as a reason to wait to invest in Japanese equities should decline, thus increasing the positive sentiment about the market.

(From: Japan Equity Outlook 2020: Overcoming the Four Concerns: https://insights.nikkoam.com/articles/2019/12/japan-equity-outlook-2020)

Governance reform still intact: Activism or engagement?

Until recently, activists in Japan were often synonymous with “hostile suitors” or “greenmailers”: generally perceived as foreign and not always welcomed. However, we believe 2019 was an important year when the line between activism and “corporate engagement” began to blur in the eyes of the public.

The change in public perception towards activist shareholders coincided with the relatively aggressive stance that well-established Japanese companies took to enhance shareholder value. Such companies included Itochu (hostile takeover bid for Descente Ltd), Yahoo Japan (voting down the re-election of Askul Corp’s CEO) and HIS (hostile takeover attempt for Unizo Holdings).

Activism is no longer considered taboo in Japan, in our view, and it is seen increasingly as a social mechanism necessary to create value.

Some highlights for shareholder engagement and activism in 2019 were:

- Institutional shareholders took a tougher stance at annual general meetings (AGMs); for example, 345 companies saw their proposed agendas opposed by votes of more than 20 percent, a record high. (Source: IR Japan)

- An all-time high of more than 200 institutional shareholders, including activist hedge funds, expressed their intent to present proposals to corporate management teams. (Source: SMBC Nikko, in FY2019 as of 10 October 2019)

- International investors successfully brought back Lixil Group’s ousted CEO.

- Star Asia Investment’s merger proposal with Sakura Sogo Investment marked the first ever hostile acquisition in the REIT space.

- Corporate buyback plans increased 90% YoY in FY2019 (Source: Nikkei). This included Sony’s JPY 200-billion buyback plan, as well as Olympus buying back approximately USD 800 million of its shares held by Sony. US activist hedge funds are shareholders of both companies.

- Toshiba, which has many activist funds among its shareholders, opted to buy out three of its four listed subsidiaries in a bid to convert them into wholly-owned units.

Government to continue pushing for reform

The previous revision to the Stewardship Code in 2017 called for greater transparency of proxy voting results. This led to institutional shareholders taking a tougher stance towards companies which manifested itself in a higher number of “against” votes at shareholder meetings. The next revision to the code, scheduled to take effect in 2020, is expected to result in a push for even greater transparency, with shareholders being urged to disclose the reasons for their voting decisions at AGMs.

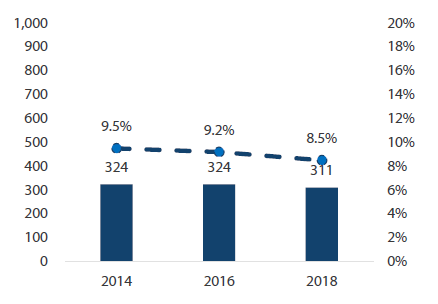

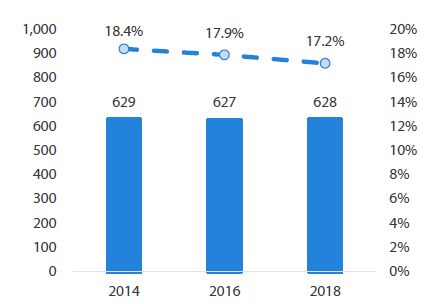

The issue of parent-subsidiary dual listings is another topic the government aims to tackle, potentially in its future revision to the Corporate Governance Code. The government now views parent-subsidiary dual listings, an arrangement unique to Japan, as a corporate governance issue as they can result in conflicts of interest between parent companies and the minority shareholders of their subsidiaries (see Chart 5 and Chart 6). Requiring companies to have independent directors on their board is one of the measures being considered to protect the economic interests of minority shareholders. We believe significant value can be created if companies take proactive action to resolve potential conflicts. For example, parent companies can take over their listed subsidiaries at a premium to gain full ownership; Bloomberg reported that the recent takeover premium was around 20%.

Chart 5: Number of firms with listed parent companies

Source: Council on Investments for the Future at the Prime Minister’s Office as of March 2019

Chart 6: Number of companies with controlling shareholders

Source: Council on Investments for the Future at the Prime Minister’s Office as of March 2019