Over recent weeks, some West Texas oil price contracts have fallen below zero (apparently for want of storage) and this event rather neatly helps to emphasize that, in the near term at least, the impact of COVID-19 has been overwhelmingly deflationary for the global economy. With GDP in a variety of countries down between 10% and 30% over a matter of weeks, it is of course not surprising that the impact on the commodity markets has been deflationary. However, there remains a great deal of discussion as to whether the After Covid World will see more deflation, or inflation, or simply “nothing different”.

At one level, Central Banks are of course ‘printing a great deal of money’ and therefore one would tend to think that in the longer term this should be inflationary, but as many point out the Central Banks’ response to the GFC was not inflationary, at least for the CPI…..

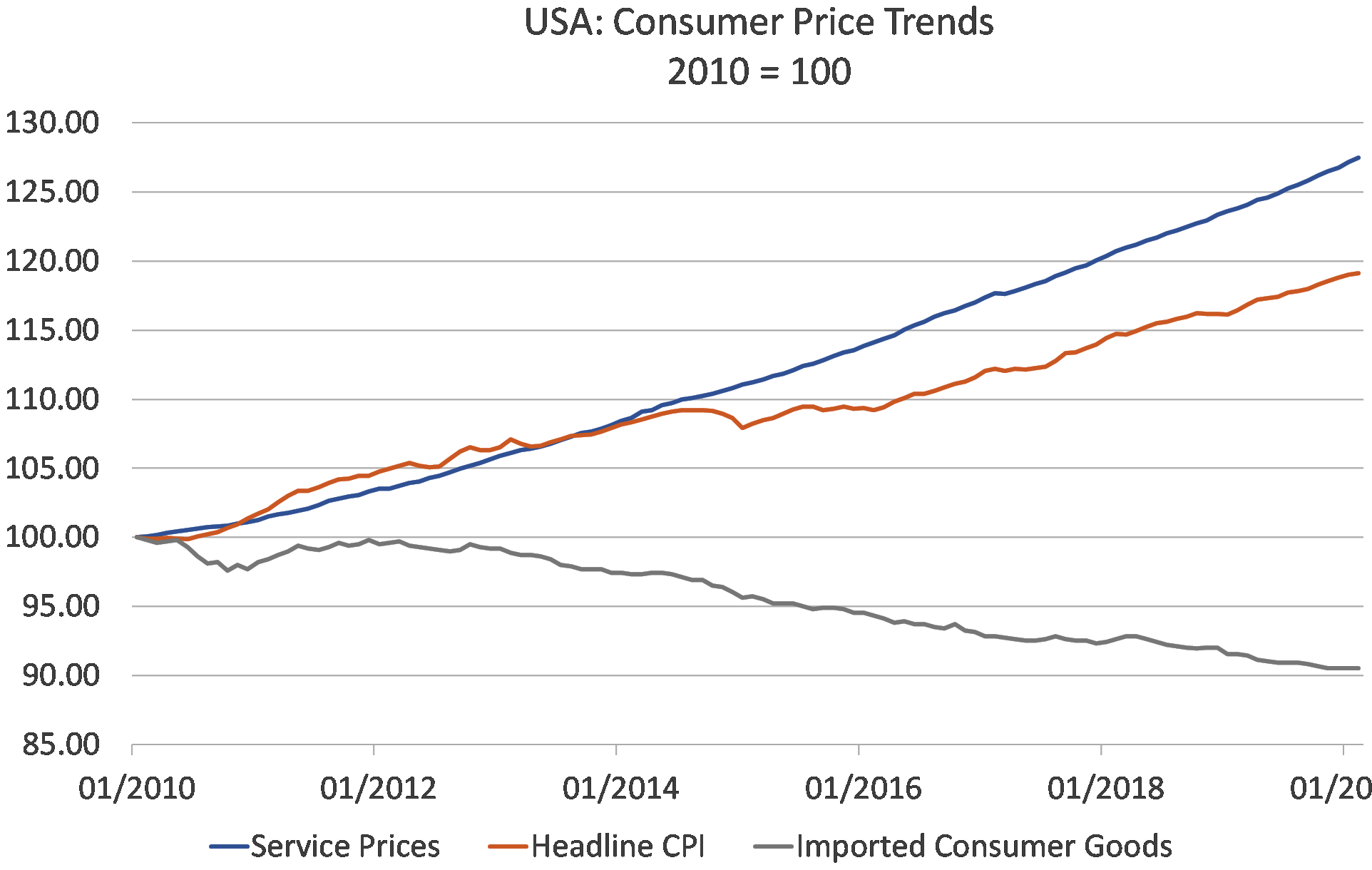

To our minds at least, the official CPI has always been a slightly random concept. Within the index, there are things that one buys nearly every day but there is also that “half a TV or a third of a car” and other items that we perhaps do not buy every year. Notionally, the CPI measures the average cost of living, but we suspect that no one is ever really average in this respect and we probably all have our own unique CPI baskets and costs of living. Therefore, in our view, it is often a mistake to focus solely on the rather arbitrary headline rate of inflation and instead we have long favoured splitting the CPI into two distinct ‘product groups’, namely non-traded goods (chiefly service sectors) and traded goods (chiefly goods, the prices of which are set by the interaction of the external factors and the country’s exchange rate).

USA: Consumer Price Trends

% change over week, 3 day moving average

The crucial message contained within the chart is that there was persistent inflation in the service sectors but also deflation in goods prices throughout the 2010s. The much lauded ‘stability’ in the headline data was therefore rather misleading, in that there was clearly price instability in both sectors, albeit in different directions. With this historical performance and analysis in mind, we can relatively easily identify what are likely to be the four or five key factors that are crucial to determining inflation rates in the future

We can certainly assume (unfortunately) that over the medium to longer term, unemployment rates will be higher than before the Crisis and one could therefore assume that wage bargaining power will be lower for employees, although we would add the important caveat at this point that some of the rise in unemployment may in a sense be “voluntary”, in that some people may simply wish to remain isolated for fear of catching the disease. Workers may demand a Covid-premium on their wages to supply labour in a now more dangerous world

Along with labour costs, the other primary cost for producing services are land prices / rents. We fully expect that land prices will decline as a result of the C-19 crisis, as unemployment rates rise (thereby reducing household aggregate incomes and potentially creating forced sellers in the markets) and bank lending standards are obliged to tighten by the banks’ own capital constraints.

This argues that, over time, the price of producing services should therefore tend to decline as the price of the necessary premises moves lower but this will likely take some time to occur, not least of all because companies will tend to look at the historical cost rather than present value of their premises when thinking about their actual costs of production. Moreover, in the near term, we suspect that the supply of services may take longer to recover than the demand for those services as lock downs are eased. It will be interesting to see which happens first in NZ now that the country has begun to ease its restrictions.

Indeed, in the near term, it is certainly not inconceivable that the level of demand for services will rise (particularly with government fiscal spending help) faster than supply can physically respond, especially if government working restrictions remain in place, people are slow to re-enter the work force (and more likely if worker benefit levels compare favourably with the level of wages on offer), or capacity that was lost during the Crisis phase is not rebuilt. Indeed, we must wonder just how many restaurants will in fact be able to re-open immediately in the AC world, with the result that the Post Covid-19 World may see capacity constraints and some higher prices even in the service sectors.

At this point, we should also consider the activities, or lack thereof, of the ‘Disrupter Companies’. Over recent years, the effect of these new entrants has been deflationary for selling prices (as well as hugely deflationary for incumbent industry profits and incomes….) but we must remember that relatively few of these companies are themselves profitable or even cash flow generative – most require injections of either direct credit or capital / credit via their VC / PE partners. It would be our assumption at this time that there will be less money will be available for these essentially speculative ventures in the World that comes after Covid, if only because the lenders will need time to recover and replenish their own capital following the Economic Slump. The lack of actual or perceived threat from disruptor companies will hand pricing power back to the existing companies in a number of service sectors and this too could be inflationary in the near term.

On balance, we would tend to assume that there will be less inflation and possibly even deflation in the service sectors over the medium to longer term, but in the first year or so, we suspect that we could in fact have more inflation or little change in pricing trends.

Turning to the goods markets, we believe that it will be the situation around China’s economy that ultimately determines the trajectory of goods prices, even in the Western economies. Historically, China’s corporate sector has hitherto operated with persistent financial deficits of a scale that, until the last few weeks, the rest of the world would have found inconceivable. These financial deficits have occurred in part as a result of the massive boom in capital spending that China embarked upon, and in part because China’s companies rarely attempt to ‘profit maximize’ in a Western sense. China’s model has prioritized scale and employment over corporate profits, just as did Japan and Korea at similar stages in their development cycles.

One of the seemingly counter-intuitive results of the operation of China’s economic model has been the inverse relationship that has come to exist between China’s rate of credit growth and the country’s export prices. During successive domestic credit booms, of which there have now been many, China’s companies have tended to both build more capacity and use cheap credit to allow them to sell at prices that in the West would not be considered optimal. We would shy away from calling this predatory pricing but simply a result of the different model that is being used.

Moreover, because China has become a global price setter, it has been China’s model that has set global goods prices, to the probable benefit of Western consumers in the short term but the considerable disadvantage of China’s Western corporate competitors and their employees.

Crucially, we suspect that, as a result of the damage that has been inflicted on China’s banks, companies and local governments by the Pandemic, it will likely be many years before China’s economy is in a position to enjoy another credit boom. Therefore, we doubt that many of China’s companies will have the funds to either build more capacity or even to run large operating deficits in the near term. In fact, we suspect that many companies will need to close their operating deficits, potentially by raising their selling prices.

Moreover, we can also hypothesize that many Western companies will wish to shorten and consolidate their supply chains, perhaps by re-shoring even this results in an increase in their effective costs. We must also wonder what the state of global politics / trading relations and tariff policies will be like in the near future (we can almost see a world of regional trading blocs amongst countries with similar economic systems & experiences with COVID-19). In this new world, we can easily imagine China’s export prices rising for what may be quasi structural reasons.

For many years now, we have frequently attributed a number of unfortunate characteristics of the modern global economy to the almost unprecedented divergence between traded and non-traded goods prices that has developed and which we showed in the chart above (the precedents being Japan in the 1980s and the US in the 1920s). These characteristics have included the ‘hollowing out’ of domestic production sectors, weak real wage growth and rising income inequality, high house prices relative to earnings, and weak overall productivity trends, all of which we believe occurred because of the over-expansion of the service sectors and under investment in the secondary sectors in response to the revealed price signals that are implicit in the chart.

If “After COVID-19” we enter a world of rising goods prices and ultimately falling service sector prices, then we can assume that the ‘gap’ between these two lines will by definition close and potentially restore some degree of longer term balance to the economy by addressing some of the factors described above. This would be a painful but ultimately good thing in our view, although it will require portfolio managers to modify their ‘style’.

In summary, the COVID-19 shock has of course been deflationary for global prices in the near term, but it is however not yet clear whether the Post COVID world will be inflationary or deflationary. Over the longer term, it is our belief - and to an extent our hope - that the Post COVID world will see some deflation in the service sectors but inflation in the goods sectors. We do certainly expect that the long period of global goods price deflation will soon come to an end and we also view it as entirely possible that, in the first initial phase after COVID, we will see continued or higher inflation in the service sectors as aggregate demand recovers faster than supply, with the result that markets may well experience an inflation shock in 2021-22 before the situation transforms itself into a ‘reversed’ form of the Goldilocks scenario, in which service prices fall but goods prices rise.