In many countries around the World, workers are now being at least partially paid by the state and government guaranteed loans are being provided to companies that the credit markets would otherwise not lend to, given the credit risks involved and low yields on offer. Admittedly, the system is working better in some countries than others – China’s banks are clearly doing immense national service quite effectively at present, while the US banks are perhaps struggling to overcome capital adequacy and bureaucratic constraints on their ability to act.

In such a system, the capital markets are no longer being tasked with allocating capital, and they themselves have in any case become somewhat illiquid as market makers have been obliged to remove capital from these particular divisions of their businesses. In fact, we would argue that, in what is now a non-market wider economic system, it is not clear just what role the financial markets fulfil at this time, which in turn rather begs the question what exactly are the financial markets doing at this juncture aside from the minor roles of providing a gauge of (investor) confidence, employment for those that work in the oligopoly of financial market related companies, a speculative arena, a modest source of income for savers, and a useful diversion for those stuck at home with no sport to watch?

Of course many people rely on activity in the equity and debt markets for their daily livelihood, many savers require high and rising asset prices after perhaps saving too little of their incomes during the late 1990s and 2000s, and, as Employee Stock Options have grown to become a key part of the overall remuneration of many Corporate Executives, many company managers also need to see higher stock prices whenever possible. Meanwhile, governments around the World that are facing large budget deficits and high existing debt burdens need-ultra low yields simply so that they can appear to be solvent. Finally, public sector pension schemes the world over are under-funded and dependent on high & rising equity prices – be they in US Municipal Government, European State Pensions, or the Australian super schemes.

Superficially at least, the world and of course most governments themselves all now appear to have a vested interest in maintaining asset prices and we suspect that this has been the driver in a number of – we believe – crucial developments in markets over the last decade or so.

For example, in the wake of the Sendai Earthquake and Tsunami, the Bank of Japan began buying large quantities of JGBs, primarily from the commercial banks. In the mainstream press, this buying was intermittently portrayed as simply another attempt at QE, but we remain convinced that the real reason that the BoJ entered the markets so aggressively was so that JGB duration and even credit risk could be transferred from the capital constrained commercial banks – that in theory would one day have to mark their investments to market – to the central bank that faces no such constraints. In a sense, the BoJ moved to eliminate market risk in the JGB market but, in so doing, we believe that it undermined the market’s very purpose. The overt ‘socialization’ of the JGB markets ultimately led to the suspension of all price discovery in the JGB markets that has left the JGB markets as almost ‘forgotten’ or ‘dead markets’ to investors.

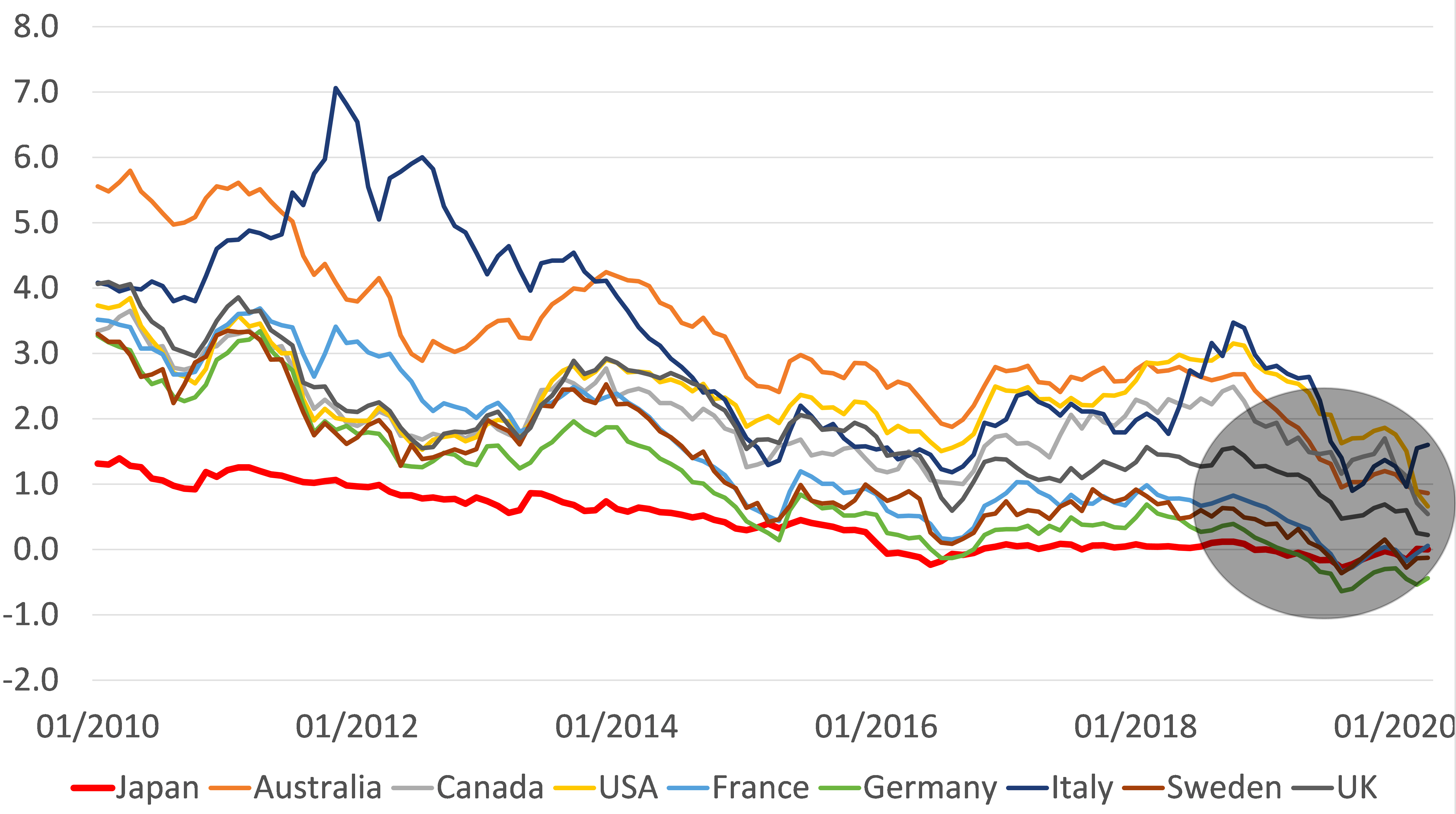

As well-meaning and perhaps even ‘necessary at that point in time’ as the BoJ’s actions were in 2011-12, we must wonder if this de facto total suspension of the JGB market’s functioning was the start of what has now amounted to a ‘Black Hole’ within Global Bond markets that has since sucked many other countries and markets into the same position - most notably in Europe.

The ‘Black Hole’ in Bonds

10 year yields % pa

From the point of view of their “clients”, we would argue that at zero yields, bonds either become of no use to end-user savers that need income, or merely assets that investors have to buy because of regulatory requirements, or assets that one buys in the hope of making a capital gain. Once yields become negative, the only reasons (aside from regulatory) to buy bonds become either seeking a positive carry for those institutions that can leverage off what may be more negative short terms rates, or an opportunity for those subscribing to the ‘Greater Fool Theory’ (i.e. that there will be someone out there who will buy the bonds from you at an even higher price between now and the bonds’ eventual loss-making maturity). In such a world, ‘real savers’ become alienated.

Of course, government issuers undoubtedly welcome the cheap funding costs that zero yields provide and they probably adjust their spending plans accordingly but, having the financial system’s “numeraire” set at zero with no price discovery must subvert the market and distort the capital allocation process within the wider economy. In particular, within the real economies, zero rates encourage the continued operation of Zombie companies that tie up productive resources, thereby negatively impacting trend GDP growth and real income growth in the economy. Supporting Zombie companies will maintain the status quo (which in Japan is undoubtedly a pleasant place for many of its older residents) but it does detract from economic growth and the prospect of wealth creation for many of the younger members of society.

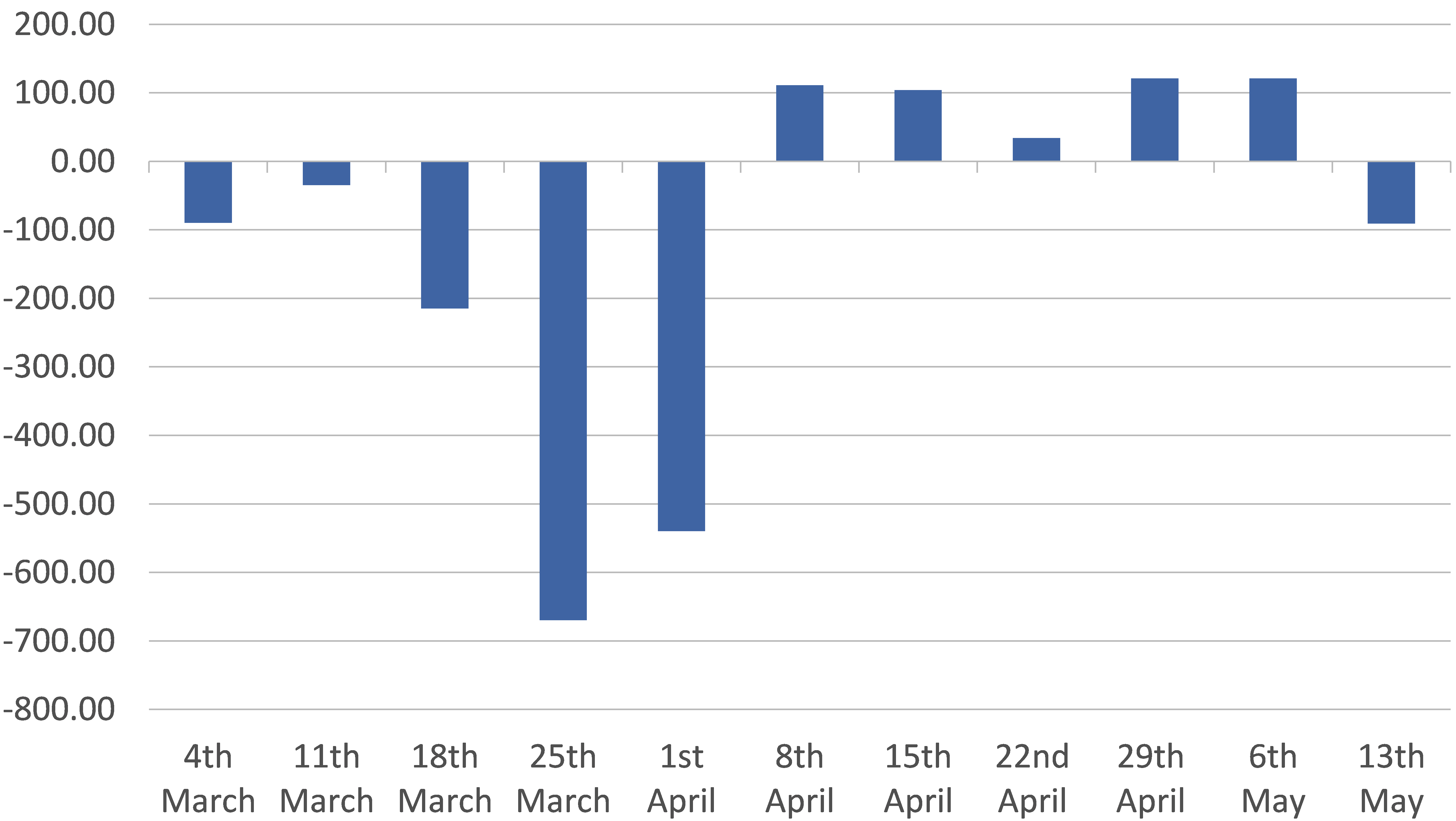

The second example of massive and we would argue fundamental market intervention occurred much more recently when the Federal Reserve, which had previously been downplaying the Covid-19 Crisis, suddenly entered the US debt markets for a day or two of sharp falls in the equity markets and removed $1.6 trillion of Treasuries from the markets in a matter of days. Naturally, the sellers of these bonds received the Fed’s newly minted cash and much of it was subsequently re-purposed into either the equity markets directly, or into the corporate bond markets. Thereafter, a number of highly rated / big name companies were able to issue significant quantities of corporate bonds (even though many did not in fact need the money from an operational standpoint) and there duly was a surge in equity buybacks thereafter. According to work published by Deutsche Bank, there have been almost $150 billion of equity buybacks over recent weeks, led by Apple’s $50 billion programme.

USA: Net change in Treasuries

Outside of the banking system USD billion over week, nsa

The Fed’s ‘monster QE’ in late March was certainly effective in supporting the equity markets but, by causing the balance sheets of the major banks to ‘bloat’ by more than 12% at a time when they were already facing capital adequacy constraints, the unintended consequence of the action was to reduce the availability of USD bank credit to many real world borrowers (particularly SMEs) and foreign entities.

According to the DB data, there were $60-80 billion of equity buybacks in April, but we estimate that C&I lending by banks to SMEs increased by only around half that amount despite the crisis and the SME’s sector’s need for urgent funding in order to prevent unemployment rising. The equity markets undoubtedly benefited from the buybacks but, at some point in the future, at least some part of the political system will ask whether it was efficient or even morally justifiable for Apple to spend more buying back stock in a month than the banks lent to Main Street companies in their time of need? By focussing on the short term, the equity markets may be storing up (political) trouble for their future.

Economists are fond of saying that there is no free lunch and we believe that a further significant intervention by the central banks will have adverse consequences for not only the availability of credit in the US real economy, the sustainability of the EZ as the ECB’s balance sheet expands and places an ever-increasing burden on the German and Dutch banks (which have to fund the ECB at negative rates), or ultimately on China’s balance of payments which appears vulnerable given the country’s already remarkably over-monetized financial system.

Therefore, we would argue that as 2020 continues, the US and others are going to decide whether they are really going to go the ‘whole way’ into a socialization / underwriting of the markets (whatever the long term consequences for the economy, politics and wealth equality), or they are going to have to re-think the sustainability of the Fed Put or underwriting of markets.

For investors, since the mid-1990s, the Fed Put has allowed the ‘buy on dips’ strategy to work and, in such a world, we might wonder why people bother supplying labour when they could have sat at home and simply bought stocks. However, quite soon the authorities are going to have to decide whether to go “all-in” on their short-term support measures for markets whatever the costs, or look to re-instate free markets by withdrawing their support and allowing price discovery to occur. It feels to us that we may be at an important moment in global financial history.