Unfortunately, there can be no getting away from the fact that the Covid-19 virus is gaining ground in the USA once again and that around 6-10 states look to be entering a period of ‘exponential growth’ in their numbers of new cases. At present, financial markets seem to be unsure how to react to the Covid data – it seems to us that most market participants are simply choosing to assume that there will be no further lock downs, and that in any case the consequences of contracting C-19 are now very much less.

To us, this view seems to be overly naïve but nevertheless this seems to be the view that has been adopted by markets for now and as a result we can note that consensus economic forecasts now suggest that Global GDP in 2023 will be the same as it would have been had the virus not escaped from its origin. To us, this seems unlikely but we have a different view on the long term effects of the Covid Crisis.

If, however, the markets and the wider economy are indeed going to choose to believe that the Covid War is over (if only because of the performance of the equity markets and the message offered by the media), then we can suggest that there will likely be a sharp - if probably only temporary - snap-back in aggregate demand as households move to spend some of the $500 billion windfall that they have recently gained from the government’s response to the crisis (and this amount is net of wage income losses that have so far been experienced).

We have built a relatively simple model that suggests that if people do decide to believe that the Covid-19 War has passed, even if this is only for a period of time, then we should get a post-war boom in certain consumer-focussed sectors. Admittedly, we very much doubt that companies – anywhere - will seek to increase investment in the near term given the uncertainty in the real economy and the desire to continue with zaitech activities but we can easily believe that households will attempt to spend more when they can. There is without doubt a degree of pent up demand in the system that will be released when it is perceived that the Covid-19 war has been won.

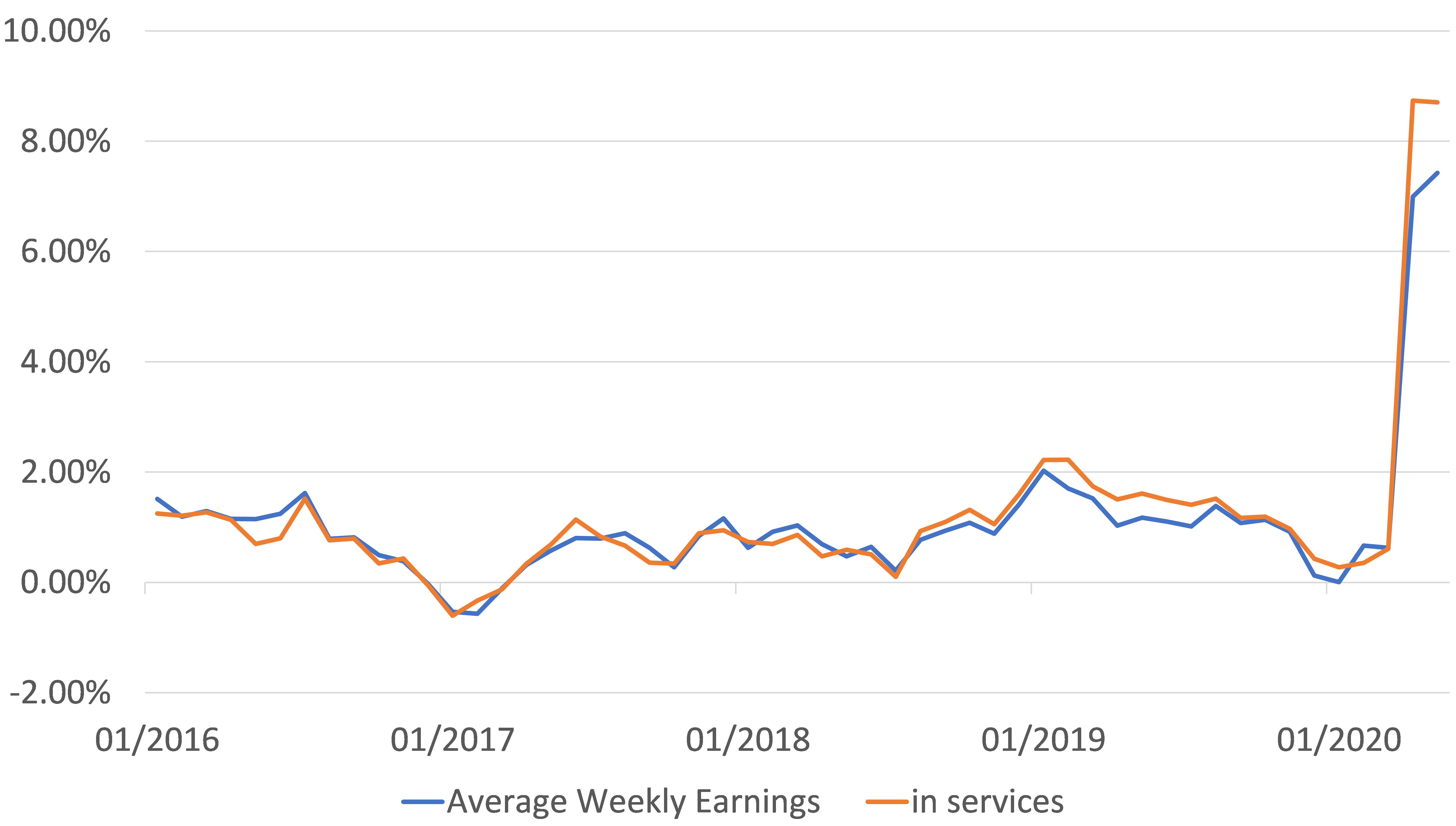

The release of this pent up demand is likely to put capacity and utilization pressure on those parts of the economy’s supply side that have managed to survive and re-open. We strongly suspect that many companies will likely be looking to raise their revenues (by higher prices if possible), and in any case we must note that wage inflation rates are already rising as a result of the impact that the generous payments that have been provided by the government through the benefits system have had on the labour markets, and the incentive to withdraw labour supply in the low-income sectors. When the Post-war boom comes, we expect it to be inflationary for the US service sectors.

USA: Average Weekly Earnings

% yoy

Does this mean that we should fear inflation in the near term, and of course a policy response from the Fed? Aside from the proximity of the elections, we suspect that the Fed will in fact be allowed to take a generally benign view of any resurgence of inflation in the domestic sectors because the higher inflation in the service sectors will likely be offset in the headline CPI data by a period of goods price deflation emanating from the PRC.

This is because, rather than providing funding to the demand side of their economy, China’s authorities have immobilized an immense amount of credit into their corporate sector so that the latter could cover its large operating cash flow deficit while restarting production and – most importantly of all for the CCP – employment. So far, the PRC authorities have been successful in this endeavour, but this has created a ‘glut’ of supply which has manifested itself in stronger export shipments but very weak import trends, a surging current account surplus, and continued export price deflation. Indeed, our Gravity Index, which seeks to quantify the impact of China’s economy on the rest of the World, confirms that the PRC is acting as a deflationary headwind to global growth.

China: AHEL Gravity Model

average = 0

In the near term, we find that the reflation of China’s supply side, rather than its demand side, is resulting in a burst of goods price deflation globally (particularly given the extreme levels of inventories relative to sales elsewhere in Asia).

We would suggest that the differing policy responses in the US and China has created an intriguing situation. The US is supporting demand but not supply, China the reverse, and we believe that in the near term the outcome will likely be rising service sector inflation in the US but goods price deflation, a situation that will likely result in a stable and therefore financial-market-friendly headline rate of inflation.

In short, we may find ourselves recreating the Goldilocks Scenarios of 1995, 1999, 2003, 2009, and 2016-17, when goods price deflation from the East in effect hid rising inflation in the West and thereby allowed the latter to expand unhindered by inflation worries. These were of course good years for risk markets (particularly those that were accompanied by QE or QE-like monetary regimes at the Federal Reserve).

Naturally, none of what is occurring is sustainable – the Fed cannot print money to give to people ad infinitum and there must be limits even to China’s ability to create credit but for now, there is a chance that Goldilocks may join the markets for a mid-year Holiday, assuming of course that the virus does not keep her away.

We must admit that there are other near-term risks aside from just the virus to this surprisingly positive near term outlook. There could easily be a surge in credit defaults as a result of the impact of the virus so far that, by attacking the plumbing in the system, finally force either the US and / or PRC credit booms to stop. With yields so low, savers are clearly not being rewarded for taking default risk and hence even only a few credit defaults could change the credit supply landscape quite radically. This scenario is certainly possible, although we suspect that, at a practical level, QE should override / minimize these risks by removing financial constraints from even the most unlikely of would-be borrower.

Another risk to this Goldilocks Scenario could come from domestic politics. The virus and other tragic events have clearly provided a very unfortunate backdrop for the unrest in the US at present but we suspect that rising inequality, weak real wage trends, and a growing resentment of the elites had created a situation that was in any case ripe to ignite. Ultimately, political forces are going to have to shift to deal with some of the economy’s longer term issues and the news that the stock buybacks in March and April exceeded the amount of credit provided to the recession-bound real economy will make the whole Zaitech game vulnerable to a political backlash at some point. However, these risks are unlikely to appear in the markets’ consciousness in the near term.

Internationally, it is clear that the cold war between the USA and China will heat up after Bolton’s dropping of his own form of political bomb. The US Administration may well look to broaden the range and scope of its economic sanctions against China, which might limit China’s own room for manoeuvre with regard to its domestic policies. Higher trade tariffs could of course also prevent PRC deflation from offsetting US inflation. These risks should not be underestimated.

Finally, the big risk that perhaps we all now face is that the demand for money crumbles in the QE countries. This is certainly a risk facing Japan, China and now the USA. All these countries have been creating money from “thin air” in order to support zombie companies and finance things that were not needed. Consequently, there is always the risk that some event – be it political, natural disaster, or economic - will finally convince savers that the money that has been created from nothing has “no value”, with the result that we see capital flight into hard assets, alternatives such as Gold, and presumed safe-haven currencies. If people will no longer accept the liabilities that the central banks create in order to fund their asset growth, then the whole game will be over, but this too seems an unlikely threat in the near term.

In summary, commentators are fond of saying that we are operating in uncertain and unprecedented times and there is undoubtedly truth in this statement. Clearly, there are many risks that could disturb markets – and which may well disturb markets over the longer term but, in the near term, there may well be a window of opportunity for nimble investors if markets decide, if only for a while, that the virus doesn’t matter and that we can enter a new period of Goldilocks growth.